Acceleration, Conspiracies, Caricatures

Notes from a month of movies and essays: Silicon Valley archetypes, America’s paranoia, China’s retro-nationalistic fantasy, and the stubborn need for optimism

This past month I’ve been reading, watching, and traveling, and I want to share a few things that stayed with me. Inspired by Celine Nguyen’s “everything I read this month”-ish posts, I’m trying a looser, more freeform style here.

Normally, I burden myself with an archaic idea of publishing: essays should be timeless, addressed to some imagined perfect readers. But this time I’m setting that aside. Think of this as me writing across the table and talking to you.

Since late July, I’ve started the Roots of Progress fellowship, read some remarkable articles, and watched some films. I also began a China trip. Part family visit in Guangzhou, part intentional deep-dive into factories, AI hubs, and industrial clusters. And yes, there was one whole day spent at West Lake in Hangzhou, lingering over cups of Mingqian Longjing tea (the tea picked before Qingming Festival). That deserves its own essay, so I’ll leave it aside for now.

Below: a few reviews, reflections, and side notes from what I’ve been watching and reading—

Movies

Mountainhead

Eddington

Detective Chinatown 1900

Articles

selections from The Roots of Progress fellowship

Mountainhead:

I watched Mountainhead with my podcast friends, and we even recorded an episode about it (in Chinese). I feel compelled to write because the film is unusually direct: it’s about today’s Silicon Valley, an accelerated one, but still struggling to convince the rest of the world to follow its pace.

The film is produced by HBO and marks Jesse Armstrong’s directorial debut—he, of course, being the writer of Succession. Armstrong is arguably the most gifted storyteller of power in our time. Now he turns his eye toward the most power-concentrated place on earth: Silicon Valley. Mountainhead dissects the figures at the helm of today’s accelerationist tech culture and sketches a new, unsettling vision of the Valley. I recommend it not so much for its artistic brilliance, but for its almost anthropological precision in capturing Silicon Valley’s tech bro ethos.

The plot is simple but claustrophobic: four tech titans, close friends, gather in a Utah luxury villa—calling themselves “the Brewsters,” a nod to the PayPal mafia. Among them, Venis, the founder of a social media empire, launches an AI-generated content tool. Within hours, it is weaponized to spread political disinformation, plunging the whole world into a deepfake crisis.

The entire drama never left the retreat house. The dialogue often feels like eavesdropping on the All-In Podcast or some private chat we are not part of—equal parts bravado and banter, sincerity and loneliness. These men, powerful yet isolated, can only connect with each other. Armstrong has said that before making the film, he read books on Sam Bankman-Fried, watched documentaries on Musk and Zuckerberg, and was struck by the absurdly blunt, nervous cadence of All-In. That voice haunted him until he knew he had to script it.

Each character in Mountainhead is a composite of real Valley figures:

Venis (note the not-so-subtle nod to “Penis”) combines Musk and Zuckerberg. He runs the world's largest social platform, dabbles in brain–computer interfaces and rockets, commands immense resources, yet cannot form a human bond with his newborn son.

Jeff evokes Sam Altman and the AI new elites: brilliant, ethically ambivalent, but personally humiliated—(a “cuck” in 4chan terms), his glamorous girlfriend openly dates others while clearly with him only for his money.

Randall is a philosopher-king hybrid of Paul Graham, Peter Thiel, Steve Jobs, and Marc Andreessen. He pontificates endlessly with Greek and Roman analogies, dismisses the nation-state, champions transhumanism, and preaches the network state.

Souper, the least powerful and poorest of the group, evokes Jason Calacanis of the All-In Podcast: thoughtful and soft-spoken, yet periphery. Among these ultra-billionaires, he serves as the organizer, providing emotional labor to others while enduring casual bullying. His nickname "Souper" is deliberately ironic, suggesting his net worth is so minuscule compared to the others that he might as well have "soup kitchen money."

Today’s Silicon Valley operates under a logic very different from that of five or ten years ago. Hubris, fear, and confusion dominate its ideological space. Out of this atmosphere emerges a new archetype: an engineering-minded masculinity—technically omnipotent, rational, unmistakably American—that wields enormous political power yet remains trapped in its own myths of acceleration.

Accelerationism is a theme I am fascinated by.

I was born and raised in China, came of age in the United States, and have worked in tech in the Bay Area. I see both places accelerate, but in different ways. In earlier writing, I’ve described China’s technological development as a form of “time compression.” China’s growth drives toward an ideologically defined endpoint: a rejuvenated, Tianxia-inflected order with a neo-Confucian turn, fused with the extreme instrumentalism in its engineering state. Silicon Valley’s acceleration, by contrast, remains ideologically unmoored. Its enthusiasts know mainly what they reject—degrowth, wokeness, the status quo—but have yet to articulate what they are accelerating toward. That absence of a horizon is, to me, its most telling feature.

And this is exactly the predicament of the four characters in the film—fictional stand-ins for Silicon Valley’s most powerful leaders—who find themselves unable to sell any political vision and techno-optimism to the world. They are confronted with the embarrassing fact that no one trusts them anymore.

The film also probes Silicon Valley’s masculinity problem. Among the four men, how much of the banter, scheming, and posturing—the constant performance of “primal” maleness—arises from instinct, and how much is just acting? Mountainhead suggests the distinction is almost impossible to draw.

In short: if you’re interested in Silicon Valley’s shifting culture of power, its accelerationist fantasies, and its fragile sense of self, watch Mountainhead. Then tell me what you think.

Eddington

(The following content contains spoilers)

What unsettled me most about Eddington was not just the film itself but the split it created among my friends. After watching, we realized we had essentially seen two entirely different films (!). One friend, a New York liberal, left impressed—she felt the movie had pushed her to confront her own blind spots and to momentarily inhabit the mental world of a conspiracy-theory victim. I, on the other hand, felt slapped in the face. In the second half, the narrative swerves into psychodrama, staging grotesque conspiracy theories like horror tropes and allowing them to hijack the film itself.

Our group chat exploded into days of debate because we were so confused. What was this film actually about? Were we being played by the director? Were we inside a meta-troll, a cinematic trick designed to make us argue like doom-scrolling combatants on X? That recursive confusion, of course, may have been the director’s point.

For context: Eddington, directed by Ari Aster, premiered at Cannes in 2025 before its July release.1 Set in the spring of 2020, it’s a neo-Western black comedy unfolding in a fictional New Mexico town under lockdown. Before watching, I expected something closer to Nomadland or Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri—a moral portrait of forgotten people in divided America. Instead, the film is nothing like that. And this is what angers me.

What I take from the film is this: the director lures you in precisely because you care, only to tear up that social contract and sneer at you for caring. One example makes this clear. At first, the story hints at sympathy for Black Lives Matter: a Black police officer is framed by white colleagues, seemingly a setup for a redemption arc that might confront systemic injustice. But no such resolution arrives. Instead, the officer is nearly killed by a mysterious drone, an abrupt sci-fi intrusion that derails the narrative. Conspiracy escalates, drones descend, and the moral scaffolding—good versus bad, right versus wrong—collapses into absurdity.

When I tried to explain the film to a friend, I reached for an analogy she’d understand: it’s like watching a labor-rights drama about women workers in Shenzhen, only for the final act to reveal they’ve all been abducted by aliens. What could have been ethical storytelling dissolves into sci-fi-y spectacle.

Stylistically, Eddington recalls Buñuel’s Exterminating Angel. It names America’s wounds—violence, inequality, misinformation, environmental precarity, but refuses to meet them with empathy. Instead, it reduces them to absurdity, inviting the audience to laugh, despair, or simply shrug.

Technology receives the same treatment. The town’s mayor, played with oily charm by Pedro Pascal, champions renewable energy, solar panels, even a data center to revive the local economy. Yet each idea is played for sneer and irony, as if the very notion of technological progress were ridiculous in small-town America. What I despise most is this clever disdain, a posture that refuses to imagine adaptation or change.

This year, I’ve become more deliberate about resisting certain “smart” works—whether essays or films—that approach social issues from a frozen, condescending stance of observation. That posture may be easy to perform and seductive to embrace, but it is ultimately evasive and damaging. I know optimism is harder, especially when reality feels unbearable. But I also know we can’t afford the luxury of nihilism.

Detective Chinatown 1900

Detective Chinatown 1900 (唐探1900) is one of the strangest films I’ve seen this year—and also one of the most revealing. What fascinates me is how, when it comes to racial representation and historical fairness, Chinese popular culture often barrels past the carefully worded debates happening in the West. Instead of nuance, it gives us the most caricatured, problematic depictions imaginable. On one level this is understandable: China, as a largely homogenous society with strong cultural uniformity, has never undergone the kind of sustained domestic debates over race that define the U.S. experience. Yet the sheer obliviousness on screen remains breathtaking, at times even embarrassing.

The film is set in 1900 San Francisco Chinatown, against the backdrop of the Chinese Exclusion Act and yellow peril racism in the United States. Into this setting the script throws everything at once: Qing officials dispatched by Empress Dowager Cixi to assassinate revolutionaries; a Holmes-style Chinese detective looking for work; Chinatown gangsters trying to justify their power; rough Irish immigrants eager to drive Chinese workers off the land; a racist white Republican politician chasing electoral victory; and Sun Yat-sen’s supporters smuggling weapons to Hong Kong to fund the uprising.

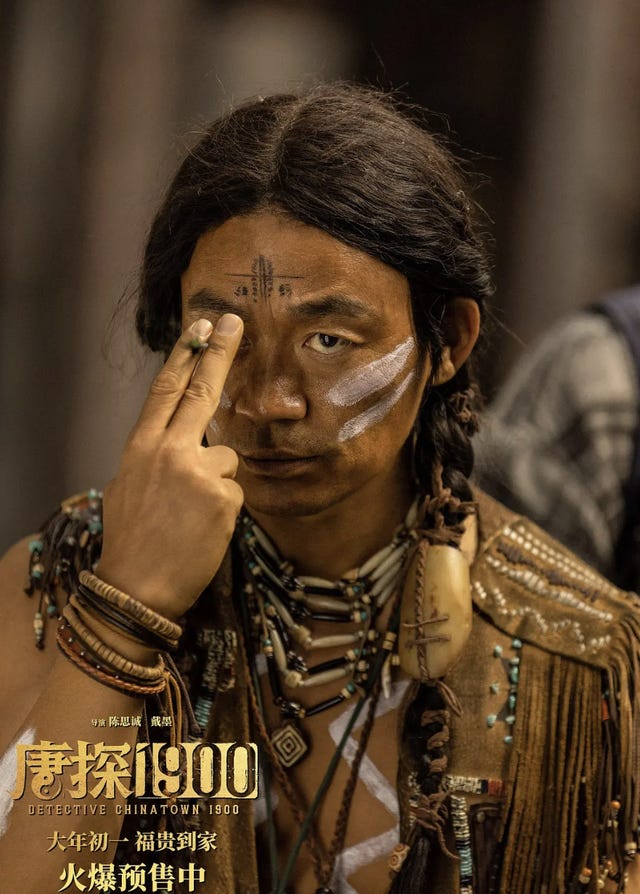

And then—most bizarrely—comes a “noble savage” figure played by Wang Baoqiang. His backstory: the only son of a Chinese railroad worker killed in an accident, he is adopted by a Native American tribe. He grows up speaking Chinese with a Hebei accent—presented as an “Indigenous American Chinese.” Wang’s character is one of the most racist, caricatured portrayals I’ve ever seen on screen. It was so absurd that as I watched and I told my partner that “AI can’t make this shit up.”

But Detective Chinatown 1900 is not only about race or revolution. It is also a retro-nationalist revival fantasy—a kind of cinematic porn that screams: look how China once suffered, how its people were humiliated, and how it is no longer so. America in 1900 is refracted through the director’s Marxist class-struggle lens, populated with downtrodden Chinese workers and scheming, greedy American capitalists and politicians, all staged alongside stubbornly corrupt Qing officials and spotlighted Chinese revolutionary heroes. The film wants to be about Sun Yat-sen, about transpacific railroad labor, about diaspora politics—but its real message is about how proud you should feel that today’s China is no longer the Qing empire of 1900, when Chinese people had to sacrifice in foreign lands because their own country was powerless. America’s cruelty becomes the backdrop for a comic, patriotic, China-centered tale. The result is overstuffed, chaotic, and yet oddly revealing in its ambition.

The Detective Chinatown franchise, directed by Chen Sicheng, began in 2015 with a murder mystery set in Bangkok’s Chinatown. Each sequel shifts to a new “exotic” location: New York, Tokyo, and now San Francisco in 1900. The formula recalls old Hollywood franchises like Indiana Jones or early James Bond: globe-trotting adventures that “discover” and “explore” foreign worlds while reaffirming the hero’s centrality. The twist is that the gaze has flipped. Now it is China doing the exoticizing—rendering Thais, Japanese, Americans, and the mixed demographics of 1900s California as caricatures.

Which raises the question: is China entering its own Victorian moment in popular culture?2 The very genre of detective fiction is itself deeply coded with Victorian rationalism. Only this time, the figure of rational discernment is no longer a pipe-smoking Englishman but a Chinese-style Sherlock Holmes. And just as Britain in the 19th century grew stronger, projected influence outward, and produced popular culture designed to give its audiences national pride through worldly tales of British centrality—like a Victorian explorer bringing back curiosities to impress the public at home—China today is following a similar path. Market demand pulls strongly in this direction.

Yet I remain unconvinced that China’s cultural ambition is to reshape the world into something more China-like. What I see instead is a more inward reflex: global settings used as stage sets for retelling the familiar arc of Chinese victimhood, resilience, and eventual triumph.

Essays

Beyond watching films, as you know, since late July I’ve also been participating in The Roots of Progress writing fellowship—an initiative under the broader umbrella of “progress studies”.

I’m late on my own writing assignments, but I’ve been reading some remarkable work from my cohort. Here are a few recommendations:

Lesley Gao’s essay on how a small, unnamed factory in Shaodong, China has quietly defied global inflation: not only does it produce 70% of the world’s lighters, it has kept the price at 1 yuan, 1 dollar, and 1 euro for the past 20 years.

Anton Leicht’s piece introducing a powerful framework for understanding Trump and Sachs’s approach to AI policy in the U.S.—what he calls mercantilist logic. This lens, of course, also sheds light on the H20 expert drama with China.

Heidi Huang’s on the surprising connections between our brain and immune system—including how simply watching a virtual sneeze can trigger real immune responses.

I want to note that Ari Aster is mostly known for his psychological horror films. Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019) turned him into a cult figure—both operatic thrillers about grief, family, ritual, and violence. Even Beau Is Afraid (2023), which wandered into absurdist comedy, was still driven by paranoia and psychological collapse.

To be clear, I don’t think this is a question I’m asking in earnest. But the Detective Chinatown series gives me a strong impression that its underlying message is: “Chinese people are the most rational, the most logical—and everywhere else in the world is full of savagery, scheming, and uncivilized behavior.”

I always love reading your work! Brilliantly engaging and insightful as always!

Although not a movie guy, I hung on every word. Great job!

To be fair, if 'fairness' is the right word, China's 'cinematic' language is equally condescending towards fellow Chinese. Northeasterners are typically featured in criminal dramas; peasants are either dim or malicious; the southwest and western regions usually only function as exotic backdrops, and with the nigh extinction of Qing dramas, Chinese minorities no longer feature as active protagonists, and when they're stock villains, aren't even granted leave to plot in their own language.

Being the optimistic sort, I just put it down to income disparities. Rising incomes across the regions will shift tastes somewhat. I can already spot some green shots in the animation scene. I can't ever pass up an opportunity to praise 'Slay the Gods'.