The Clock and the Rocket

Qian Xuesen's America, My Grandmother's China, Wright's California: a story about many forms of technological time travel

Last week I participated in a China tech conference at Stanford, and afterward, the speakers and organizers—intellectuals I deeply admire—went to dinner in Midtown Palo Alto. I tagged along.

It was 7pm, but the California sun hung suspended in a cloudless blue sky, extravagantly spilling light across the modernist low-rise buildings. Even the unremarkable parking lot we passed revealed itself as an understated brutalist showcase upon closer inspection.

As we walked, I overheard someone joking about Francis Fukuyama: "No wonder he could write about the end of history—he lives in Palo Alto." Some laughed knowingly. Everyone who arrives from the East Coast or other American cities makes similar remarks about this peculiar "end of history" feeling that permeates Palo Alto.

It does feel like history's conclusion materializes here: pristine, orderly, wealthy beyond measure, with every edge softened and every need anticipated. The town generates an illusion of living at time's terminus, where progress has reached its logical endpoint and now simply refines itself in imperceptible increments, like software updates that change everything and nothing simultaneously.

This temporal suspension has defined California in the American imagination for generations. When I watched the documentary The Center Will Not Hold1 about Joan Didion (another California-coded writer), I was struck by how the physical landscape of California in Joan's time hasn't fundamentally changed: the sprawling suburbia, specialty coffee shops, dramatic coastline, convertibles cutting along coastal highways.

Didion's languid sensibility became a spiritual totem for California itself—a place where a particular tension between physical environment and psychological state perpetually unfolds:

A good part of California does not seem to me to be part of the United States at all. It is a place in which a boom mentality and a sense of Chekhovian loss meet in uneasy suspension." —Where I Was From, 2003

California suspends itself between futuristic promise and perpetual disillusionment—a tension I felt most acutely when I visited the Marin County Civic Center north of San Francisco.

I made the pilgrimage after learning it was the shooting location for Gattaca—the 1997 science fiction film depicting a future with widespread gene-editing, solar panels, and routine space launches. In that cinematic universe, the Civic Center served as the headquarters for their version of SpaceX, a gateway to humanity's cosmic destiny.2

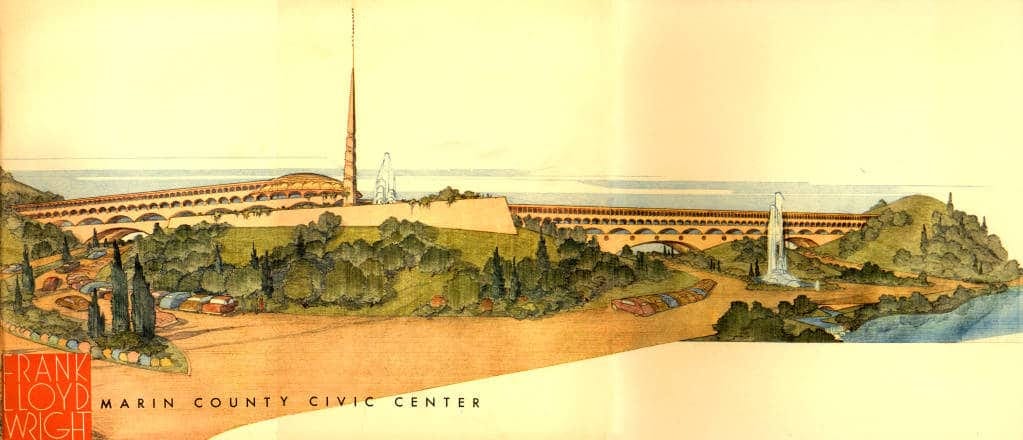

Commissioned in 1957 and partially completed by 1962, the Marin County Civic Center was Frank Lloyd Wright's final major project and his only realized government building. Designed during America's post-war era of optimism and technological advancement, the Civic Center features a distinctive blue roof—originally intended to be gold to match the summer hills—a 172-foot gold spire housing a radio transmitter, and expansive atriums illuminated by barrel-vaulted skylights. The design exemplifies Wright's philosophy of "organic architecture," harmoniously integrating the structure with its natural surroundings.

What strikes me walking through its sun-drenched corridors is how the building remains stubbornly futuristic seven decades later.

In the 1950s and early 60s, America believed technological advancement would solve fundamental human problems—not just create digital conveniences, but reshape our physical environment to create more humane, sustainable ways of living. The Civic Center represents a radical optimism—a belief that public institutions deserved beauty and that technology should serve collective purposes.

This building promised a future we never fully inhabited. California has always excelled at creating these spatial pockets that feel simultaneously retro-futuristic and perpetually present, generating the unsettling sensation that we are in a disappointing now.

When I returned to China, the sensation was different. The sheer velocity of urban transformation makes you believe that progress can unfold so rapidly that the conventional stages of industrialization might be skipped entirely—that a society might leap from agrarian to digital, bypassing the intermediate phases that took centuries to unfold in the West.

I remember my father telling me about his mother in Shandong province who walked five hours to the train station, then rode three more hours into the city, simply to buy a clock. A clock so that his siblings would know when to go to school. This was the 1980s, not the 1880s. She sewed her money into the lining of her cotton jacket to protect it from thieves on the train, who were everywhere then. The journey took all day and most of the night.

In 2025, my grandmother uses a Xiaomi smartphone. She hasn't touched cash in three years. During COVID, drones sprayed disinfectant through the narrow spaces between the residential buildings where she lives. The woman who once walked five hours for a clock now lives surrounded by machines that fly in her sky.3

I find myself fascinated by this progression compression. My grandmother never left China, yet within her lifetime, she witnessed how Chinese industrialization bent time itself.

While reading Iris Chang's Thread of the Silkworm, a wonderfully-written biography of Qian Xuesen (or Tsien Hsue-shen), the “father of China’s space and missile program.” What struck me most wasn't Qian's undeniable genius—laying the foundation for rocket science, earning tenure at MIT at 36, writing his seminal work "Engineering Cybernetics" while under house arrest during the McCarthy era (and eventually leaving the U.S. in disappointment and humiliation). Rather, I was captivated by how, through his journey from China to America and back again, Qian experienced something similar to what my grandmother lived through: a form of technological time travel compressed into a single lifetime; Although Qian’s life was only more transformative and embeded in the broader, and much more destructive political context.

When Qian enrolled at Shanghai Jiao Tong University in 1930, he studied steam locomotive engineering—in China then, railways represented engineering aspiration and national sovereignty. For Chinese students of Qian's generation, mastering railway engineering was reclaiming technological dignity in a country where most villages had never seen a train. But by 1934, Qian found himself in MIT's classrooms studying aeronautical engineering—a huge leap in technological complexity. He made the decision after seeing Japanese warplanes darkening Shanghai's skies during the January 28 Incident of 1932, when bombs destroyed factories, universities, and hospitals: whoever mastered the air would master the future.

At Caltech a few years later, Qian joined The Suicide Squad—a small band of eccentrics who conducted experiments with rockets, devices that existed primarily in the pages of Jules Verne and the imaginations of science fiction writers. Their experiments often failed spectacularly—hence the name—but “The Suicide Squad" soon evolved into the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, receiving Washington's funding and eventually becoming NASA's space program.

Qian drove this transformation—he had compressed multiple technological epochs into a single decade of intellectual development. It, to me, was almost temporal displacement, as if he had personally experienced a century of engineering evolution compressed into ten intense years.

This compression of technological time creates a fundamentally different relationship with the future. In California, I often sense a peculiar nostalgic futurism—a yearning for the optimistic futures imagined in previous decades. The Marin County Civic Center embodies our nostalgic desire for past visions of the future more than we generate new ones. It represents an America that once built physical futures—that reshaped the material world rather than retreating into digital spaces. Its ambition feels both dated and urgent, a reminder of what technological optimism once meant.

In China, futurism manifests in physical reality. The 45,000 kilometers (about 28,000 miles) of high-speed rail constructed in fifteen years, the entirely new cities rising from former farmland, the transformation of urban landscapes—all create the visceral sensation that the future is arriving in real time.

I've come to see that technological progress isn't a universal timeline but an experience that shifts across borders. The "end of history" feeling in Palo Alto and the accelerated time compression in China represent fundamentally different relationships with time itself. I collect these stories—my grandmother's clock journey, Qian's rocket evolution, California's suspended futurism—because each reveals how societies imagine progress and how time bends around technology. One generation walks; the next flies. Or rather, one generation simultaneously walks and flies, carrying both worlds within them.4

This documentary is mostly about Didion’s vibes, and I love it.

Gattaca is about a future of, arguably, techno-optimism and abundance, but also reveals invisible poverty and a lower class of "invalids"—humans who remain un-gene-edited. I felt conflicted while watching—drawn to its alluring future yet troubled by the darkness lurking beneath. The film also showed me what incurably romantic masculinity means. For the first time, I understood that these seemingly childish games of masculinity are actually about honor—that one's honor stems from having a mission, and that mission must be grand and sublime.

I wrote about my grandmother's online shopping addiction and how drones patrol her community and disseminate disinfectants during COVID in an earlier post, "China In Flux."

A brief confession: This piece of vibe writing has been sitting in my drafts for a bit and I just want to get it out. It's not meant to be a thoughtful analysis of techno-optimism or China's development path (topics I'm exploring more rigorously), but rather captures perception and emotions.

What a wonderful writing style you have! Nostalgia can be glorious, and we must not forget the past nor forget the uniqueness and the genius of every generation. We will soon have data centers in space and nuclear energy on the moon. While America builds a golden dome, China dreams of a space future.

This piece reminded me of Disney's Carousel of Progress. It's such a saccharine vision that never mentions all the horrors that technological advancement brings with it, like mutually assured nuclear destruction. But on the bright side, we do have refrigerators that connect to the internet now.

https://youtu.be/Xo4jnlvJmrk?si=bJRAh34RNWkuQqyq