Reading Breakneck from China

How diaspora readers debate China as “engineering state,” America decline, civil society’s collapse, rule of law vs. rule by man, and what it means to leave China but never let go, with remarks by Dan

Back in late September, my podcast friends and I organized another Chinese-language book club to discuss Dan Wang’s Breakneck. The book had been persistently appearing on my timeline for months. As Dan’s friend, I’ve been living with Breakneck for months—I got a copy early on, so inspired by it, wrote a book review, read countless others, and listened to at least ten podcasts. I joked with Dan that I can’t escape Breakneck. But for all that immersion, I’d mostly engaged with English-language responses. I wanted to hear how it landed with a different audience, one that shares my background and might surface what I’d overlooked.

The question driving our discussion was simple: How do we, as first-generation immigrants from mainland China, understand this book? What shifts when people discuss it in Chinese, in a space where we can speak with unfiltered rawness about the country we left but never quite leave behind?

All of the discussants in this piece have “voted with our feet.” We left China and built lives elsewhere—the book club has thoughtful friends across the US, UK, and even Japan. Yet China still makes us proud, sorrowful, and confused, often all at once. We’re the people who chose distance but can’t achieve detachment. And our podcasts (Cyberpink 疲惫娇娃 and American Roulette 美轮美换) attract a particular kind of listener: educated, diaspora, and in the American sense, liberal-leaning, but deeply ambivalent about what that means when discussing home.

After years of paying attention to “China books,” I’ll put it bluntly: for Chinese readers, there are really only two categories: books to love because they see Chinese people and China’s messy, vibrant, pulsing society; Books to despise because they reduce China to a political entity, narrated from a detached, sky-high perspective.

Breakneck sparked a wide spectrum of Chinese-language responses: Some initially misread it as “advocacy.” Once people actually engaged with the text, nationalistic media accused it of “smearing China.” Yet others felt Dan captured the essential—the pulsing, dynamic society they recognize. Still others argued that Dan misunderstands China. In our book club, we encountered all these reactions and more. Another pattern I have observed is: the readers with living experience in mainland China are obsessed with whether China truly qualifies as an “engineering state” by tallying up Politburo Standing Committee members’ backgrounds, missing that “engineering state vs. lawyerly society” is a framework for understanding in the marketplace of ideas.

Dan and I have had many conversations about his book, its reception, and the fraught process of writing about China—how the subject itself projects power even over those of us who’ve left. Perry Link captures this perfectly in his new book title: “The Anaconda in the Chandelier,” a precarious, looming presence that doesn’t need to strike to influence how you move through the room.

I shared this draft with Dan, who was kind enough to respond with thoughtful comments. I’ve put his reflections at the end of the essay. (I convinced him that, in the Substack era, such asynchronous dialogue enriches the form.)

Below, this book club covered (the bolded are my favorites):

Why Breakneck Is Striking a Nerve in America

America’s Competitive Logic and the Dark Side of Efficiency

Knowledge Transmission and the Price of Competition

Questioning the Framework: Culture, History, and Belief

China: Crony Engineering or True Technocracy?

A Debate About Breakneck’s Rhetoric

A Lawyer’s View on “Lawyerly Society”

Rule of Law vs. Rule by Man: Unpacking the Euphemisms

Voting With Our Feet: Pride, Sorrow, and the Immigrant’s Dilemma; Processing Complex Attachments with China

Distrust, Freedom, and the Limits of Prosperity

Choosing Pluralism Over Convenience

Dan Wang’s Responses

Why Breakneck Is Striking a Nerve in America

Afra: What intrigues me most about today’s book club is this question: Why does Breakneck strike such a deep chord with America’s collective psyche?

If Trump 1.0’s political conflicts exposed the fissures within American society, those fractures were already developing during the decline of manufacturing. That decline wasn’t merely an economic loss. It was a loss of identity, dignity, and what I call “producer selfhood.” The Rust Belt ceased to be just a geographic region and became a psychological image: an American soul abandoned by globalization, nostalgic for modernity itself. Now, in the Trump 2.0 context, I observe Silicon Valley undergoing a reckoning, a fundamental reassessment of China, and a recalibration of its mental models. They’re beginning to realize that what truly determines future competitiveness remains the power to “make things”, industrial capacity, and this is precisely China’s forte.

Within this pivot, Breakneck functions as a mirror to reflect America’s anxiety about its own incapacity. As Ezra Klein observed in his ChinaTalk episode:

The resurgence of American industrial policy is one hundred percent because of China. Remove China from the equation, and American industrial policy wouldn’t be resurging.

In other words, China has become not only the object of American strategic competition but also its reference point for reimagining modernity. Over the past decade, I’ve never seen a book about China appear so violently in American public discourse: cited by journalists and podcasters, debated by scholars, added to entrepreneurs’ must-read lists. Its core framework—the “engineer state” versus “lawyerly society”—not only offers a novel explanatory model but reveals the tension between American pragmatism and institutional ossification. I believe Breakneck represents the beginning of an electrifying new way to think about the US and China, especially at the society-to-society level.

Another observation in the book that particularly moved me is Dan Wang’s repeated emphasis on “China-American similarities.” Both countries are intensely materialistic, pragmatist; both hold quasi-religious faith in industry and technology; both harbor a certain collective fervor for large-scale infrastructure. Whether American elites, Chinese elites, or the Chinese masses, all generally believe their nation is exceptional and should occupy a special position on the world stage, bearing the responsibility to demonstrate their prowess. This parallel conviction is the most subtle and most dangerous resonance point between the two countries.

Meanwhile, a silent “talent war” unfolds between China and the US. The question is no longer merely who has smarter policies or deeper pockets, but who can offer the most compelling developmental narrative to the brightest minds, whose ceiling is higher, who is creating the future.

Finally, I know many reviews have mentioned this, but I must highlight a highly relevant intertextuality: the dialogue between Breakneck and Abundance. As we discussed in Reading Abundance from China (a similar book club that happened in June), that book only briefly mentions China, yet its abundance agenda essentially uses China’s construction capacity as a mirror for self-reflection. Just as twentieth-century Japan was once viewed as a projection of American economic anxiety, today’s China has become the latest instrument American elites use to diagnose their own predicament: not to understand China, but to understand themselves.

America’s Competitive Logic and the Dark Side of Efficiency

Sirui Hua (Journalist and media entrepreneur, lives in NYC): Remember Amazon embraces what Bezos said, “Your margin is my opportunity”? Meaning if your product has high margins, that’s my opportunity: I enter with low prices, crush you, and ultimately become the monopoly. From this angle, China’s current model might be the extreme development of competitive logic that American elites once envisioned.

I want to return to Afra’s earlier point: Why does this book resonate so profoundly with Western elites? On one hand, its narrative is extremely persuasive: depicting China as an efficient, goal-oriented “engineer state” that contrasts with America’s inefficient, internally conflicted “lawyerly society,” forming sharp criticism of the domestic system; on the other hand, this narrative appears friendly to China, especially in the first two chapters—extolling infrastructure achievements and development speed, making one mistakenly think it’s a hymn of praise.

But if you keep reading, you’ll find the author doesn’t shy from pointing out the “engineering state’s” dark side: the one-child policy, zero-COVID policies, social control... If these sections were directly translated into Chinese, they’d be nearly impossible to publish in China.

Conversely, this also reflects America’s current mood: pessimism about national prospects, distrust of the political system, and even doubts about “American exceptionalism.” I once chatted with a former colleague who said, “In the past, we could at least say America may not have high-speed rail, but we have democracy and freedom. But now? We have neither high-speed rail nor democracy and freedom.”—This obviously oversimplifies reality, yet genuinely reflects the emotional shift.

Knowledge Transmission and the Price of Competition

Yiting (tech worker, lives in London): China’s material abundance, especially its rapid development in technology, leaves a profound impression on visiting Americans. Just two years ago, many believed China could never lead technologically; now, America must acknowledge: China actually has something.

What struck me most was the emphasis on “knowledge transmission,” not just invention itself, but how knowledge passes through generations. This strangely reminded me of Japanese anime Demon Slayer: humans battle demons; human demon slayers die, but their spirit and techniques endure through succession; demons, meanwhile, are like marble buildings: majestic, eternal, yet once built, fixed and unable to evolve. When the strongest demon falls, the entire system may collapse, but as long as one person lives, the Demon Slayer Corps never dies. This dynamic, self-renewing transmission might be a metaphor for the Chinese model.

This reminds me of conversations with friends: in the past, we sought jobs at tech companies for rapid growth, but now, at a certain stage, people prefer monopolistic enterprises because only when companies can “lie flat” do individuals get breathing room. China has long occupied the intensely competitive end of the manufacturing value chain, where ordinary people must work harder than others just to get by. The question is: Is this the life Americans want?

Imagine if the US government suddenly announced: “Abolish patent protections, dismantle the lawyer system, introduce full competition.” Short-term, productivity might surge. After all, America currently “lies too flat.” But the lawyer class represents not only efficiency-obstructing “obstruction power” but also the moat of existing advantage-holders. Thus, we face a contradiction: As an individual, do I hope to be the one who can lie flat, or the one perpetually competing? And if I’m a leader, do I want subordinates to be comfortable or ceaselessly striving?

Questioning the Framework: Culture, History, and Belief

Vanessa F: I’m skeptical of the “engineering state vs. lawyerly society” framework. Dan Wang’s starting point is: since the 1980s-90s, Chinese leadership has predominantly had engineering backgrounds (Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, Hu Jintao, etc.), thereby shaping the nation’s engineering orientation. But I wonder: Does this obsession with engineering and infrastructure truly originate solely from top-down political culture?

Just last night, as I prepared for tonight’s discussion, my father called from China. He rarely contacts me proactively. For twenty minutes, he excitedly described his observations in Wuxi’s Taihu New City: how wide the roads are, how good the greenery, how beautiful the buildings, how grand the construction scale. I asked him: “What’s the occupancy rate?” He paused, then countered: “Does that matter? It’s built so magnificently! America and Europe simply can’t do this! Look at your New York, nothing new for decades.”

This conversation made me suddenly realize: this fixation on engineering and infrastructure doesn’t seem limited to Politburo Standing Committee backgrounds but has permeated the entire social fabric. The book also mentions that even in impoverished Guizhou province, the government built numerous bridges and tunnels, and local villagers still take pride in them, despite these facilities not immediately improving their livelihoods.

This raises two questions:

First, is this “engineering culture” the result of 1980s-90s political elites’ top-down shaping, or a deeper historical continuation?

Second, before engineers became leaders, did Chinese society already possess some natural preference for technology and manufacturing?

Since the Opium Wars, has China’s obsession with science and technology long been rooted in the national psyche? Or does traditional Chinese governance culture inherently contain “social engineering thinking”? For instance, Confucianism emphasizes “rule by man” rather than “rule by law.” The imperial examination selected generalists rather than legal experts—is this governance tradition more enduring than the “engineer state”?

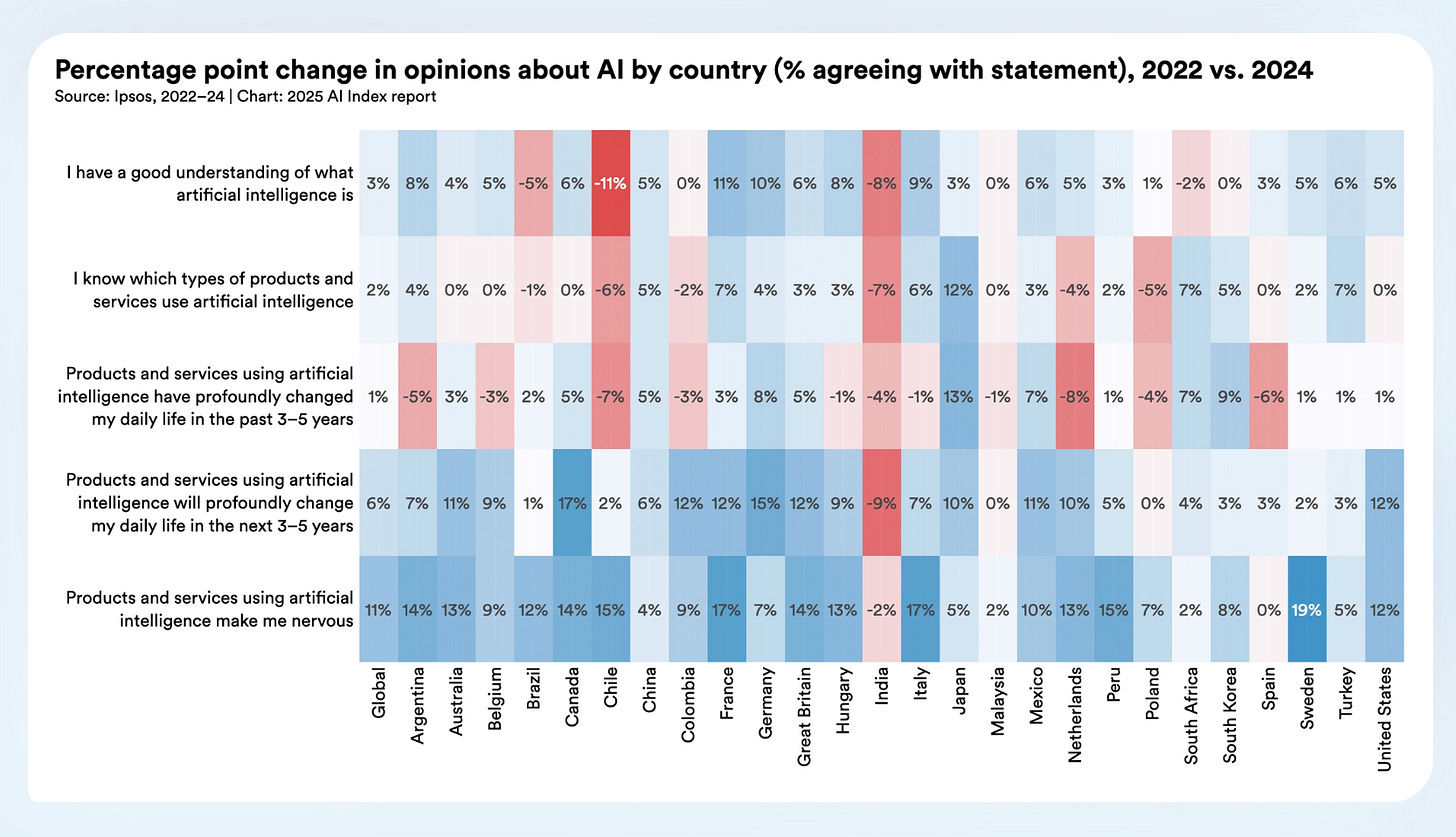

As for the American side, Dan Wang claims both China and the US are obsessed with technological progress and grand projects. For China, this undoubtedly holds true; but for America, I have reservations. Beyond West Coast tech elites, American culture overall is more defensive and nostalgic—longing for the golden age of the 1990s rather than eagerly building an AI future together. Stanford’s AI Index Report shows global public attitudes toward AI are polarized: China is optimistic, America broadly pessimistic. If even belief in technological futures has wavered, can the “techno-nationalism” narrative still stand?

China: Crony Engineering or True Technocracy?

何流|Liu He (research fellow at the Hoover Institution): First, is this book “pro-China”? Popular discourse often mistakenly calls the author “Wang Dan (王丹),“ that widely known dissident from the 1980s-90s. While nationalistic media like Guancha.cn deliberately call him “Wang Dan 王旦” (using a different character), they intentionally avoid sensitive associations.1 Interestingly, it’s these most likely “pro-China” voices that criticize Dan Wang most fiercely. I read a Guancha comment stating: “This person is utterly useless to China. You think one book will make America wake up, reform, strive, and catch up with us? You’re delusional. These people make a living from anti-China rhetoric, persistently badmouthing China. Gordon Chang is already viewed by Americans as a Chinese spy—let Americans deal with these bastards themselves.”

Such rhetoric abounds on Guancha. From this perspective, Dan Wang is clearly not regarded by China’s nationalist camp as “one of us.” But the question is: Is China truly his “engineering state”? I don’t think so.

Mao-era suppression of experts and intellectuals is well known; during the Deng, Jiang, and Hu periods, technocrats indeed held positions in the upper echelons. But among today’s CCP Politburo Standing Committee members, only Ding Xuexiang genuinely has an engineering background, and even his engineering experience was brief. Though Xi Jinping once studied chemical engineering, as a “worker-peasant-soldier student,” his educational experience was special; after graduation, he immediately entered politics, never engaging in engineering or technical work. Calling him an engineer based solely on two years of irregular higher education seems far-fetched.

More critically, if China were truly governed by engineers, why does reality overflow with policies appearing unoptimized and lacking precise calculation? For instance, why start with real estate, an economic pillar? And why in places like Guizhou do they spend hundreds of millions building luxurious school buildings yet struggle to guarantee teacher salaries? Behind these phenomena lies not engineering rationality but the collusion of power and capital—in a system lacking fiscal transparency and oversight, infrastructure becomes a channel for local officials and their relatives to siphon state funds. Rather than an “engineering state,” it’s more accurately a “crony engineering state.”

A Debate About Breakneck’s Rhetoric

Xiaoyang (ML engineer, lives in NYC): I’ve actually been pondering: Why does this book read so “pro-China” in the first chapter, yet increasingly ambiguous thereafter? The core reason is that Dan Wang’s assessment of Chinese politics essentially still views it as a libertarian territory-state—but this doesn’t sound good, so he substitutes a more pleasant term: “engineering state.”

The key isn’t whether “building” itself has been moralized. “Getting things done” is elevated to supreme virtue, requiring no questioning of purpose, cost, or distributive justice. This reminds me of dialogue from a Jinjiang cadre novel (晋江高干文): “What’s wrong with building? As long as there’s money, building is good. Building is always better than not building.”2 But when Shuozhou City in Shanxi Province constructs luxurious, uninhabited apartments, problems emerge.

Dan Wang’s framework evades the truly crucial question: How do technocrats ascend to power? Can they become governors through elections? In China, they can become provincial governors; in America, they struggle to enter mainstream politics. Rather than exploring this institutional difference, he directly reduces China and America to the binary opposition of “engineering state” versus “lawyerly society,” using easily transmissible language to package an old question about state capacity and social checks.

Sirui Hua (Journalist and media entrepreneur, lives in NYC): I’ll respond to the question of whether “this book is pro-China.” This narrative has even been absorbed by the Chinese government. A few days ago, Carney said at an event: “China is a country governed by engineers with deep understanding in areas like emissions reduction.” Global Times immediately excerpted this passage as high praise for China. Clearly, “engineering state” has become a kind of transnational complicit rhetoric—satisfying Western imagination of an “efficient other” while aligning with China’s self-positioning as a “technological powerhouse.”

Afra: I want to add to this: The “engineer state vs. lawyerly society” narrative is extremely popular in Silicon Valley, possibly because American engineers and tech investors need some form of endorsement. From Elon Musk to Silicon Valley moguls, they deeply feel institutional constraints and crave political empowerment. Dan Wang’s book provides them validation: Look, when Chinese engineers hold power they can build high-speed rail and dams; we’re dragged down by lawyers, unable to move forward.

Also, I actually want to defend this framework. If the core argument of a book can be abstracted, compressed, and distilled into a single phrase, that’s evidence of its power. It’s like reading Thomas Kuhn: you may forget every chapter, but paradigm shift will stay. That kind of condensation is not a necessary rhetorical strategy. When a concept can ignite a wide public discussion, it means it has tapped into a genuine, underlying anxiety. Honestly, I’d buy a hundred copies of this book for my American friends—it dramatically lowers the cost of our cross-cultural conversations

Xiaolan (Co-host of CyberPink, lives in NYC): Completely agree. It uses contemporary language to repackage eternal tensions in governance: How should state and society coexist? But I’m also thinking of another book—The Narrow Corridor. Its core argument is: Only when state and society maintain relative balance in dynamic contention can individual freedom possibly grow. In China, the state always runs ahead of society; in America, society has long since left the state behind. Dan Wang’s binary, though concise, may obscure this more complex reality.

Haihao Wu: I’d like to defend Dan Wang somewhat. His book actually distinguishes between natural sciences and humanities/social sciences. He points out: freedom is crucial for humanities and social sciences; but under authoritarian systems, paradoxically, social sciences might actually be more “developed”—because people are forced to package political demands in technical language. He cites examples from the Soviet Union and contemporary China.

Therefore, “engineering state” carries pejorative connotations in his writing. It describes a kind of intellectual laziness: refusing to enter the complexity of humanities and social sciences, instead using half-understood natural science logic—like Social Darwinism—to explain society. Liu Cixin’s Three-Body Problem embodies precisely this tendency. Dan Wang isn’t praising this model but revealing its dangers.

A Lawyer’s View on “Lawyerly Society”

A (Lawyer, lives in NYC): Frankly, I finished this book somewhat disappointed. The author opens with “America is a lawyerly society.” Yet throughout, he never truly explains what “lawyerly society” actually means.

As a commercial lawyer, I want to discuss this framework’s problems from a practical perspective. First, in the real world, clients’ highest praise for lawyers is often not “legal expertise” but being sufficiently “commercial.” Being “commercial” precisely means not being bound by legal texts. If you obsess over statutes all day, clients find you obstructive; truly favored lawyers are those who solve problems like engineers—knowing when to persist, when to let go, rather than endlessly haggling over details at the negotiating table. Anyone who’s participated in large, complex transactions understands this.

My clients are mostly investors, rarely with legal backgrounds. I enjoy collaborating with them, yet I extremely dislike dealing with opposing counsel—the same process often takes ten times longer.

Second, regarding the notion that “America is a litigious society,” clarification is needed. True, American litigation is frequent, but this doesn’t stem from combative national character but rather institutional design. Government retreats from the public sphere, outsourcing regulatory enforcement to private litigation. For example: Chinese companies listing in the US frequently face shareholder lawsuits alleging securities law violations and inadequate disclosure. Companies exhaust themselves responding, at high cost. But this isn’t Americans deliberately targeting Chinese firms; rather, the SEC lacks capacity to proactively oversee every company—in China, such responsibilities fall to the CSRC; in America, they rely on private lawyers through class action lawsuits for enforcement.

The law provides litigation incentive mechanisms, allowing private parties to continuously challenge in courts. Personal injury lawyer ads saturating New York subway stations are natural products of this system. Therefore, the problem isn’t the “lawyer society” ideology but the inefficiency and friction caused by privatized state functions under “small government” logic.

Rule of Law vs. Rule by Man: Unpacking the Euphemisms

Sirui Hua (Journalist and media entrepreneur, lives in NYC): Actually, returning to the point, I find this narrative very compelling, but peel back one layer and you discover: it’s really talking about rule of law vs. rule by man, or “governing the country according to law” vs. “using law as a tool for governance.”

The book dedicates a chapter to the one-child policy, which I think is an excellent example. Is this engineer governance? Song Jian, who promoted this policy, though a brilliant scientist, one of the founders of China’s missile and aerospace engineering, was neither a demographer nor sociologist. His ability to push the policy through relied on his scientific status and political resources. That this policy became fundamental national policy wasn’t because of “engineering thinking” but because China’s policy-making lacks institutional and legal constraints.

Dan Wang actually mentions this, but he packages it in a more marketable concept. I don’t know if this is clever or helpless, but it’s quite interesting.

Xiaolan (Co-host of CyberPink, lives in NYC): Right, I also think this is essentially the art of language. For instance, he says “supply-side vs. demand-side,” which really means “what the people need”—but the Chinese government doesn’t care about demand economics. If stated directly, this sounds very sharp; but wrapped in terminology, it appears very “academic.”

While reading, I kept thinking about “power.” Robert Moses is particularly interesting—he’s a monster grown from America’s so-called “lawyer society.” Never elected, merely a technocrat, yet he became America’s greatest builder. What’s his legacy? I’d love to hear everyone’s thoughts.

Voting With Our Feet: Pride, Sorrow, and the Immigrant’s Dilemma; Processing Complex Attachments with China

Afra: Now let’s discuss a more personal topic. Dan Wang mentions in the book that his parents brought seven-year-old him from Yunnan to Canada in the early 2000s, later moving to America. They often wonder: seeing China develop so rapidly now, do we regret not staying?

Everyone here is an immigrant from China living in America or other countries—I see podcast listeners in Japan and the UK. To some extent, we’ve all “voted with our feet”—our physical bodies long ago left China. Yet China as homeland remains an inescapable intellectual and emotional anchor. How do we process these complex feelings about China?

I constantly experience this complicated emotion: seeing China lead globally in solar, batteries, and electric vehicles, the “new three items,” seeing China become “cool China,” seeing many experience future shock when visiting China, I can’t shake off that knee-jerk sense of pride. But simultaneously, seeing other things, like reading the One Child Policy chapter in Breakneck, I feel immense pain, because only China’s concentrated power could accomplish something so fucked up. Less than three years ago during COVID, we all experienced political depression triggered by China’s pandemic policies, even though we weren’t in China at the time.

I know Dan Wang writes about China using very rationalist language, but in the section about cycling through Guizhou, I detected much emotion. I sensed that attachment to land, regret over change, profound love for those real places and people. This might also be my own emotional projection onto Dan’s book.

So I’m particularly curious: How does everyone handle this state where pride and sorrow coexist? How do you view today’s “declining America” and “rising China”?

Haihao Wu: You articulated this beautifully. One revelation from this book for me is: you can simultaneously hold both emotions.

Previously, I always felt pressured to take a stance: “Do you support China or not?” Especially in some leftist groups, if you say China has developed, you must preface it with “I don’t support the regime.” But Dan Wang made me feel you can seriously examine this issue—see the advantages while firmly criticizing backward aspects. These two emotions can completely coexist.

Afra (paraphrasing A’s comment): Our lawyer friend A said he can tell from the book that Dan Wang is a very gentle person. I completely agree. I’m thinking especially of the section about his parents’ immigration. That honesty, that “small regret my parents feel wondering if they chose wrong,” and the final reconciliation, all very gentle and vulnerable. But he feels this part wasn’t developed enough. He also wrote in his own book review that he hopes to see more such personal narratives in the future.

The Ghost of Civil Society: A Story of Lost Possibility

何流|Liu He (research fellow at Hoover Institution): Regarding “pride in China,” the recent Yarlung Tsangpo River dam project reminded me of someone: Xiao Liangzhong. Twenty years ago, he opposed dam construction on the Jinsha River and Yarlung Tsangpo River. Back when China’s civil society was just beginning, with scholars, NGOs, media—many people opposed it. The reasons were numerous: illegal processes, environmental destruction, economic irrationality, cultural devastation, forced relocation, and impact on global ecology.

Xiao Liangzhong organized people nationwide to submit proposals at the Two Sessions, even writing to Premier Wen Jiabao. Later, the environmental assessment department said: “You don’t have an environmental impact report; the project cannot proceed.” The matter was shelved.

But in 2005, Xiao Liangzhong suddenly died at only 32—about the same age as many present today. Cause of death remains unclear. For twenty years afterward, no one mentioned this again.

Until last year, the dam project suddenly resumed. By the time news was announced, local residents had already been forcibly relocated. Those media outlets, scholars, and civil society members from years ago can no longer speak. Write proposals to the Premier? Even more impossible.

So when I see the Yarlung Tsangpo River’s “magnificent project,” I feel no pride whatsoever. Only heartache, only anger, only thinking of Xiao Liangzhong dying with eyes open, thinking of so many people’s years of effort, all wasted. In the early 2000s, everyone thought China’s civil society was just beginning, heading toward greater freedom; yet today, reality has completely reversed course. Facing such reality, regardless of China’s mega-projects, I find pride very difficult.

Loving Countries Like Things, Not Family

Yiting (tech worker, lives in London): When we say “pride in our motherland,” what are we really talking about? I think often, Chinese people’s feelings toward their country resemble those toward family—like my pride in my children, my parents. This pride doesn’t tolerate criticism: if I tell outsiders my parents are bad, that’s unfilial; if others criticize my child, I get angry.

But why can’t it be like supporting a soccer team? I support a team; if they play terribly today, I’ll curse the coach and players, but nobody thinks I’ve stopped loving the team. Why can’t it be this way with countries? A country isn’t a person; it’s a thing. We should love it the way we love “things”—appreciating its bright spots while criticizing its failures.

Vanessa F: I’ve pondered this question for a long time. I work in AI, and now America’s security sphere constantly discusses “how to suppress China.” Hearing this in meetings, I feel conflicted inside.

Also, I think Chinese people’s feelings toward China differ from Americans’ feelings toward America. One reason might be different historical lengths.

My grandfather was born in 1940 in a Henan village. His China is: Japanese invasion, civil war, Great Leap Forward, Cultural Revolution, Reform and Opening... His ability to live today’s life constitutes his entire relationship with the state. But current Americans’ relationship with their state might be: “Buying houses was easy in the ‘60s; now housing prices are too high.”

This difference in historical memory genuinely shapes completely different citizen-government relationships.

Moreover, when I look at China, I feel a kind of romanticism. Because China’s modern history spans only one or two hundred years, I naturally wonder: “What will China be like in fifty years? A hundred years?” But in American political discourse, even “five years from now” already counts as long-term. Few people seriously consider “what will America look like in a hundred years.” This difference in temporal sense also affects emotional depth.

Distrust, Freedom, and the Limits of Prosperity

Xiaolan (Co-host of CyberPink, lives in NYC): I particularly want to add: Dan Wang’s sections involving personal experience are actually the book’s most honest parts. Especially when he left China, writing about his family’s “voting with feet” moment—after seven years living in China, he realized: the CCP regime’s most self-destructive core problem is distrust and fear of the Chinese people, limiting their potential for flourishing.

This is his ultimate diagnosis of China’s developmental bottleneck.”Though he used many new terms and new language to package the discussion, the conclusion is actually quite straightforward: lasting prosperity requires combining innovation with freedom. This sounds somewhat clichéd—Western economists always say it—but he tells it differently.

He particularly notes that Shenzhen’s prosperity didn’t result from state promotion but happened despite state interference—society growing itself through covert negotiation within systemic crevices. I think he articulates this very clearly.

Choosing Pluralism Over Convenience

Afra: I remember in the “Fortress China” chapter, Dan Wang says after living in China for seven years and experiencing the pandemic, what he missed most about America was pluralism.

I spent five weeks in China this August and September. This duration is peculiar, long enough that you’re completely immersed in Chinese daily life, entirely forgetting you have a parallel life in America, yet just enough to make you realize: “I really don’t want to stay longer.” I deeply understand why Dan Wang wanted to return to America after living in China for seven years.

Someone in the chat asked: “Staying in China too long, do you feel your brain getting shut down?” I do. Even though I used a VPN with completely unhindered internet access, I still felt suffocated. I’d rather give up China’s gleaming infrastructure, those life conveniences, to return to a less convenient but freer place.

Especially during the 2025 V-day Military Parade on September 03, when I happened to be home in Beijing, I remember hearing the enormous sound of jet fighters overhead, streets full of people. But simultaneously, The Lychees Road 长安的荔枝 was selling well—a novel satirizing bureaucratic culture, face culture, and imperial power overriding everything—and its film adaptation was screening. Doesn’t The Lychees Road discuss exactly the human cost behind “concentrating resources to accomplish what the emperor wants”? These two events, which happened while I was in Beijing, felt especially surreal.3

Sirui Hua: After recent H-1B news broke, the group discussed extensively: Why did everyone come to America? Previously, many might have come for grand terms like “democracy” and “freedom”; but now, more people think about smaller things: work-life balance, friend circles, even just money.

I think rather than dwelling on those grand terms, focusing on these more personally relevant small matters might be a better mindset.

Also, I’m somewhat worried: What takeaway will American elites draw from this book? Will they promote abundance, or simply grant the president greater power, letting him become “CEO of America, this giant corporation”? Currently, support for the latter seems increasingly prevalent. This unsettles me greatly.

Dan Wang’s Responses:

Reader A alleged me to be gentle and vulnerable. To that accusation, I yield tenderly without complaint.

This book club debated three important themes. How should we make sense of new stories on China’s growing technological prowess as well as its worsening repressiveness? How do we communicate these trends to a public that is eager to learn about China? And how do we connect the geopolitical to the personal? I am glad to read the discussion between so many people who are interrogating how they feel about China, and who ponder whether they have established a better life overseas, much as my parents did decades ago. So I am grateful to Afra and her podcast crew for organizing this reading group as well as the participants for sharing their thoughts.

My own thoughts about these themes are below.

First, I’ve always thought that we should straightforwardly accept the simultaneous truths that Chinese firms are growing more capable while the state grows more autocratic. I see myself fighting a two-front battle against efforts to invalidate either claim. It is astonishing that over a billion people have exited from poverty, that a few hundred million people are part of the global middle class, and a few million are members of the global elite. China’s economy is far more robust than any autocratic state’s, especially those that suffered through communism. At the same time, by virtue of being one of two superpowers in the 21st century, China has been able to extend its form of autocracy in fully novel ways. Too many people only want to see only one trend. I believe we have nothing to lose by acknowledging both.

Second, I think that we need to motivate discussions of China beyond the nature of its political system. How many times can we say that the system is autocratic and subject to the whims of one man? Is that still interesting? That’s where we should try to come up with new frameworks, like the engineering state and the lawyerly society, each with virtues and flaws. It is here that I want to call out He Liu for uncharacteristically taking a top-down view. “If China were truly governed by engineers,” he said, “why does reality overflow with policies appearing unoptimized and lacking precise calculation… Why in places like Guizhou do they spend hundreds of millions building luxurious school buildings yet struggle to guarantee teacher salaries?” I think that building first and finding economic benefits later is exactly the tendency of engineers. And it would be precisely missing the point if the outcomes would be better if the leadership were made up of “real” engineers; I think the leadership in Beijing are real engineers, and we can all observe their brutal mistakes. There is no reason to believe that a country governed by engineers would be able to achieve effective central planning. No policymaker anywhere actually would.

Third, I was most struck by Afra’s comment that she felt that, once she spent a certain length of time in China, she would feel her brain starting to shut down. I feel the same way. When I stay for long in China, I miss books (which I cannot readily order), the ability to access an unfettered Internet, and conversations with people who do not self-consciously succumb to self-censorship. But I recognize that not everyone is like me and Afra. Some people are fine with the strangulated information environment, preferring to live in more orderly streets, with richer food options, and better mass transit too. We’ll have to accept that people who vote with their feet are not all traveling along the same path. And I hope that Breakneck and Abundance will convince a growing contingent of Americans to improve the country. One outcome I am looking for is that the United States will be more welcoming to Chinese, who will in turn feel not only that they can achieve intellectual growth, but real personal flourishing too.

Think Guancha.cn as China’s nationalistic Breitbart.

Ok, dropping a bit of info about advanced Chinese online culture here: Jinjiang cadre novel here refers to a popular sub-genre on the Chinese fiction platform Jinjiang Literature City featuring romances set among elite political or bureaucratic families. These stories blend court-intrigue dynamics with modern urban settings, full of power games, patronage networks, and “officialdom” aesthetics—and are known for their melodrama, hierarchy-driven plots, and highly codified social worlds.

This movie and the novel are ostensibly about “a low-level Tang-dynasty bureaucrat racing to deliver fresh lychees from Guangdong to Chang’an with impossible speed.” But in reality, it’s about something entirely different: the subtle, coded culture of chinese officialdom, the machinery of power struggles, the cruelty of imperial authority, and a bureaucracy that behaves like a misaligned AI—unleashing a cascade of brutal, hyper-real consequences all for a few lychees. It’s a story that is unmistakably about contemporary China. Don’t let the Tang-dynasty robes fool you. And I highly recommend it.

Very interesting conversation. Three points: (1) It looks like most people in the discussion group are successful, young professionals. Probably not in the top 1%, but close to or aspiring to be members of the top 10%. I wonder how the discussion would look among a group of “median” workers. I am a retired American economics professor living in a small city in Yunnan province. My view is that life quality for median workers here is much better than it would be in a similar city in the US. (Or in Beijing). (2). I agree that Wang’s distinction between an engineering state and a lawyers’ state is important. Lawyers typically impede building and engineers naturally want to build. But, I don’t think it comes down to rule of law vs rule by law. Average people in the US often correctly believe that the expense of good lawyers prevents them from accessing rule of law. Which brings me to (3): In my view, the US is more accurately a finance guys state. For example, with enough money firms that are clearly violating the intent and the letter of antitrust law can run rings around the DOJ.

Easily the most nuanced and interesting review-discussion about the book I've seen, thanks. Now I want to write my own review after reading this.