UK's Progress Ambivalence

I entered the Britain's quiet revolution against technological pessimism

One afternoon in 2018, though I can't recall the exact date, I stood transfixed before Turner's "Rain, Steam, and Speed" in London's National Gallery. I was a fresh LSE student just arrived from California.

The painting shows a locomotive thundering through rain toward London, nature and machine blending into a single, quintessentially British vision—romantic yet tinged with the artist's evident terror at the new world bearing down. The energy was magnetic: steam billowing, wheels churning, the future itself hurtling eastward across the Maidenhead Railway Bridge. The new world is coming, the painting seemed to shout. That train, first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1844, would within two centuries reach almost every corner of the globe.

Seven years later, last week, I find myself in a Camden bar in London surrounded by hundreds of smart-looking British entrepreneurs, business leaders, and founders—80% male, as expected—gathered for an event called "Looking for Growth." But where Turner's locomotive radiated unstoppable dynamism, this room pulses with a different kind of energy: the controlled anger of people who believe their country has abandoned its most obvious obligation to grow. Despite London's extraordinary cultural wealth, despite being everything America's intelligentsia claims to admire—calm and peaceful neighborhoods, intellectual discourse, civic engagement, relatively sane governance—these technologists have gathered not in celebration but in collective action born from frustration.

The contradiction haunts me. How did the nation that gave birth to the steam engine, the World Wide Web, and the Universal Turing Machine become a place where its brightest minds must self-organize to demand the most basic economic function: growth itself?

If you know South Kensington, you understand the texture of British intellectual life—that overwhelming sense of accumulated knowledge and rational inquiry that defines the UK as a cultural force. Every weekend, the station overflows with visitors from across the globe, drawn to the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Science Museum, the Natural History Museum. Whether viewing avant-garde exhibitions or public displays, South Kensington offers some of the world's finest curation. This abundance initially overwhelmed me when I first came to London as a student. As a Chinese immigrant who had spent 5 years in the United States (mostly in California) before arriving in London, I was unprepared for the sheer density of free cultural events, the visible richness on every street corner, the sense that you might stumble upon the unimpressive building where Penicillin was discovered and a random street where Charles Dickens wrote his greatest novels while getting your groceries. London felt like a living history class, where the pursuit of knowledge seemed woven into the city's fabric. I quickly became addicted, spending what my LSE classmates would have considered embarrassing amounts of time wandering through museums that in any other city would be once-in-a-lifetime destinations.1

But scratch beneath this cultural magnificence and you discover a more troubling reality. The numbers are staggering: the UK's GDP per capita has grown by just 0.5% annually since 2008, compared to 2.2% in the United States, 6.5% in China, and 1.1% in Japan (OECD Economic Outlook, 2024). Real wages have stagnated for over a decade. Productivity growth, which is the ultimate measure of technological progress, has been essentially flat since the financial crisis. As one phrase circulating on social media puts it: "The UK is a poor country attached to a rich city." Behind these numbers lie pathologies that mirror America's institutional sclerosis: NIMBY coalitions wielding veto power over development, pension funds pursuing safe mediocrity over productive investment, centralized policymaking paired with fragmented implementation, and a cultural retreat from the innovation that once defined the nation.

At the Looking for Growth (LFG, as they called it) gathering, entrepreneurs shared stories that revealed the depth of this stagnation. Máté Kun, a European founder based in London, told me the now-familiar tale: he raised $10m in the UK for his food tech startup and is committed to building in Europe despite finding the tech environment and appetite for risk stifling, but already eyeing the US as their next move instead of Europe. Despite persisting with his company, which was doing great, he oscillates between hope for change and mourning for the dynamism he witnessed in America that simply doesn't translate to the British context.

Another on-stage speaker from Manchester asked desperately: "Where have all the magical places called factories gone? How can I change the UK so I can see myself raising a family here?" The question hung in the air like an accusation against two generations of policy choices.

Nearly every UK entrepreneur I know expresses a particular kind of solitary determination—what one described to me as “the resolve of someone swimming against not just market forces but cultural currents.” An acquaintance who worked at Entrepreneur First (EF), often called "Europe's Y Combinator," once said: "EF exists to ship European and British entrepreneurs to America for fundraising”. The United States remains the no-brainer destination for European founders, even if they plan to return and target European markets.

Having lived and worked in the Bay Area for six years, I understand exactly what he means. American innovation culture operates on the premise that failure isn't just tolerated—it's celebrated as education. Certain mantras, such as "fail fast, fail often" reflect a deep cultural belief and industrial dynamism. This tolerance for ambitious experimentation has fostered a distinct founder culture. The Bay Area has achieved critical mass: enough innovators and entrepreneurs that the "tech changes the world" ethos has become celebrated, even unassailable. British culture, by contrast, seems to prize stability and intellectual skepticism over experimentation. When Britain's brightest minds gravitate toward what people call "smart-sounding industries" like consulting and law, they're choosing careers that reward analysis over creation. The cultural signal is clear: better to be sophisticated and stable than audacious and uncertain.

Yet what struck me most about the LFG gathering wasn't despair but a particular form of patriotism—what I can only call cultural revanchism. According to their website, the LFG movement aims to "push Britain out of decline” through building, pressuring politicians, influencing policy, and organizing to "improve Britain, bit by bit." Nearly every attendee radiated genuine love for Britain. The dominant sentiment in the event felt like: "We need to save the UK right now, because nobody else will," and as they put it, “we are the cavalry.” This was anger transformed into determination—grievance about paths not taken, coupled with resolve to get the country back on track. Many spoke with what might be dismissed as techno-solutionism about energy, AI, and infrastructure, displaying something approaching a savior complex. I found myself admiring this endearing combination of ambition and devotion.2

The Industrial Melancholy

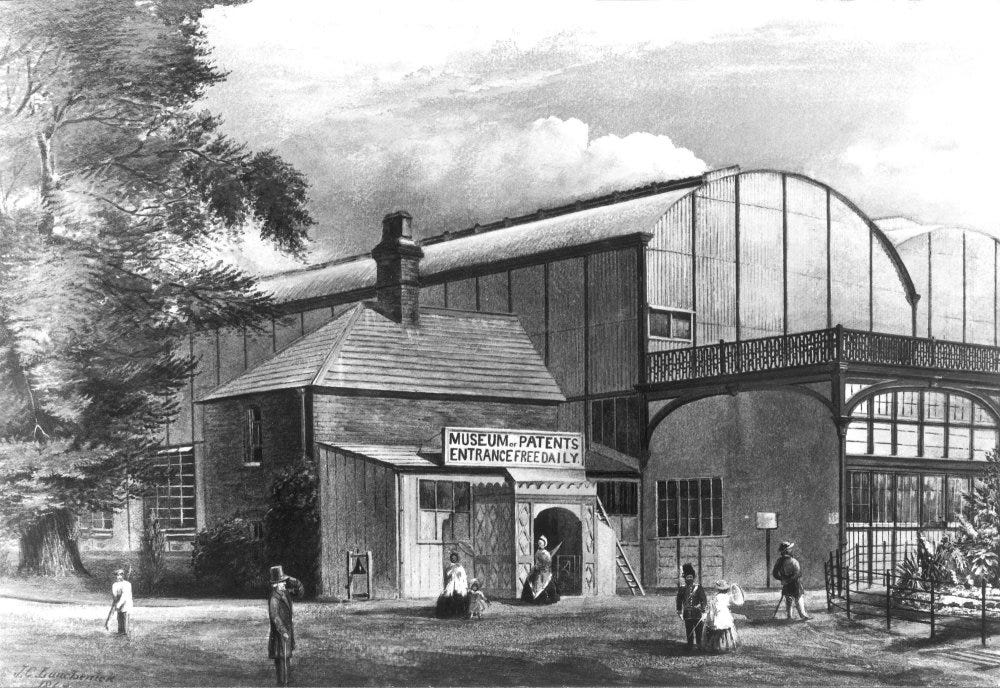

The source of their frustration I sensed in the LFG gathering crystallized for me during a recent visit to the Science Museum's permanent exhibition, "Making the Modern World." The ground-floor hall traces the evolution of industrialization from the Enlightenment to today, showcasing objects that fundamentally transformed human life over 250 years: from the first locomotive to the Apollo spacecraft to early Apple computers.

The exhibition's first half feels energizing, even sublime. Despite presenting critical perspectives on industrialization's costs, the narrative maintains an underlying sense of awe as you follow humanity's intellectual foundation from Francis Bacon to Isaac Newton, watching observational and rational knowledge transform into power—tools to measure chaotic nature, "machines for making machines," futuristic fairs like the Great Exhibition in 1851 that still sound romantic today. This first half of the narrative was particularly poignant for the viewers is that almost every breakthrough on display—from steam engines to electromagnetic theory—emerged from British minds on British soil.

But walk those hundred meters to the exhibition's end, approaching the late 20th century, and the tone shifts. The curators label 1960-2000 as the "age of ambivalence," and the narrative simply stops, never going into the 21st century. The placard reads:

"By the end of the twentieth century, the industrialised world had come to view poverty, famine and disease not as inevitable features of society, but as conditions which could be solved by technology. Yet as the pace of technological change accelerated in the late twentieth century, industrialised societies entered an age of ambivalence—of mixed feelings about technology and its role in the world. As advanced technologies affected more aspects of everyday life, anxieties about their side effects and unintended consequences undermined popular trust in the concept of progress and its promoters."

This discontinuation haunts me as if history ran out. The exhibition refuses to engage with the present, ending on a note of hollow melancholy. While other exhibition halls in the museum promise to address the future, this particular framing—treating 1960-2000, arguably the most technologically progressive era in human history as these are the decades as an "age of ambivalence"—feels like institutional surrender.3

As someone born and raised in China who has worked in the US for over a decade, I've become fascinated by a fundamental question: how do different societies organize and sustain technological progress? I find myself conducting thought experiments: imagine this same exhibition in a science museum in Shenzhen, China’s most innovative city. The ending would sound radically different—perhaps infused with the nationalistic slogans and deterministic optimism that resembles America's 1950s science fiction golden age. Chinese curators might frame recent decades not as ambivalent but as foundational, positioning today's innovations as the natural continuation of 250 years of human progress.4

This contrast reveals something crucial. My friend, a UK tech entrepreneur and former scientist, recently told me: "I feel like the UK has been gripped by a cultural war—not right versus left, but progress versus degrowth. That sign in the Science Museum clearly demonstrates that progress lost that war." His insight cuts to the heart of Britain's predicament: which cultural narrative gets to define Britain's relationship with its own technological heritage? The museum curation represents a choice that reflects structural preference by the cultural establishments: someone actively decided to frame 1960-2000 as "ambivalence" but not in other ways. Britain's cultural establishment has essentially declared technological culture suspect. This tiny corner of curation reflects specific trustee ideologies and civil service perspectives that emerged from decades of U.K.’s cuts and risk-averse governance.

This represents Britain's paradox I found compelling: the nation that birthed the world's finest educational institutions and scientists now enjoys perhaps the highest level of intellectual exchange globally, offering unparalleled resources for learning and self-development. Yet it has failed to convince its most entrepreneurially spirited young people that their technological future should be rooted in hope rather than ambivalence.

The cultural establishment controlling influential narratives—from museum curation to policy frameworks—has embraced implicit anti-tech sentiment. Referring to the most technologically progressive decades in human history as an "age of ambivalence" reveals the larger cultural trajectory through telling details—what the Chinese call zhiwei jianzhu (知微见著), seeing the grand pattern through small signs. This seemingly neutral curatorial choice actively discourages positive imagination about the future and strips legitimacy from young technologists who need what Dan Wang calls "definite optimism" to drive change.

Wang's framework suggests that "definite optimism"—a collective belief in a better future paired with actionable plans—functions as vital human capital driving innovation and economic growth. I would argue that some societies, such as the UK, require intense levels of optimism and almost toxic self-belief to foster transformative change. Culture should nurture such ambition rather than breeding what Bloomberg originally dubbed Japanese millennials as "the world's gloomiest"—a label that increasingly fits Britain's rising generation.

The LFG gathering in Camden marks the beginning of a movement that I'm eager to follow. It represents a cultural insurgency against curated ambivalence. These people aren't seeking nostalgia or dozing stability, but a movement that could become like Turner's locomotive, thundering through the rain toward an uncertain yet inevitable future.

Thank Máté Kun for filling in more details about his story. I am keen to talk with more European and British founders and entrepreneurs about technology and progress!

I recently met my college history professor and long-term mentor, Jeff Wasserstrom, in London, and we talked about our fondness for the city. He mentioned he wouldn't consider moving to any other city in the world except London—and his words left a lasting impression, making me treasure even more my opportunity to study, visit, and live here.

I also noticed LFG's approach to social media—they understand how to build movements in the modern attention economy, and of course, they have a podcast and an active X account. My only hope is that this energy doesn't remain confined to viral short videos.

As a liberal who studied history, I understand Britain's colonial legacy and the valid critiques raised by environmental and social justice movements - I was in these movements, too. I want to be clear: I'm not advocating for uncritical celebration of the past. The curators' caution about tech triumphalism is entirely understandable given the costs of industrialization we all know—environmental destruction, labor exploitation, and imperial violence. But, the UK society has developed an institutionalized pathology: a reflexive apologetic stance that treats acknowledgment of technological progress as morally suspect, and I don’t think people should be okay with that. What frustrates me about this exhibition is it left me with the impression that technology has failed humanity—that the use of technology is naive at best, dangerous at worst. To note, the decades from 1960 to 2000 brought us semiconductors, the internet, genetic engineering, and space exploration.

Let me share some examples from China. The Beijing Digital Science and Technology Museum (CDSTM), which opened in 2006, was created with a clear purpose: to "exhibit achievements and advances in science and technology and how science and technology impact social life in the past, present and future." As a young visitor, I was captivated by interactive experiences like chatting with an “smart robot” (perhaps foreshadowing my current passion for AI?) and entering a Faraday cage, where I watched high-voltage electric currents spark around the protective shield while standing safely inside. Another one would be the Shanghai Science and Technology Museum, which I visited in 2006 after its 2001 opening, also left lasting childhood memories. My research shows that this museum was deliberately centered on the "harmony of nature, mankind, and technology"—embracing progress rather than ambivalence.

we are so back

so excited to see LFG taking off and challenging this managed decline this once great nation finds itself in

"like Turner's locomotive, thundering through the rain toward an uncertain yet inevitable future."

beautiful