Story of A Beijing Vibe Coder

From burning through $50,000 in Claude Code tokens per month to building global software products from Beijing apartments—how resource scarcity is creating a new breed of super-individuals in China

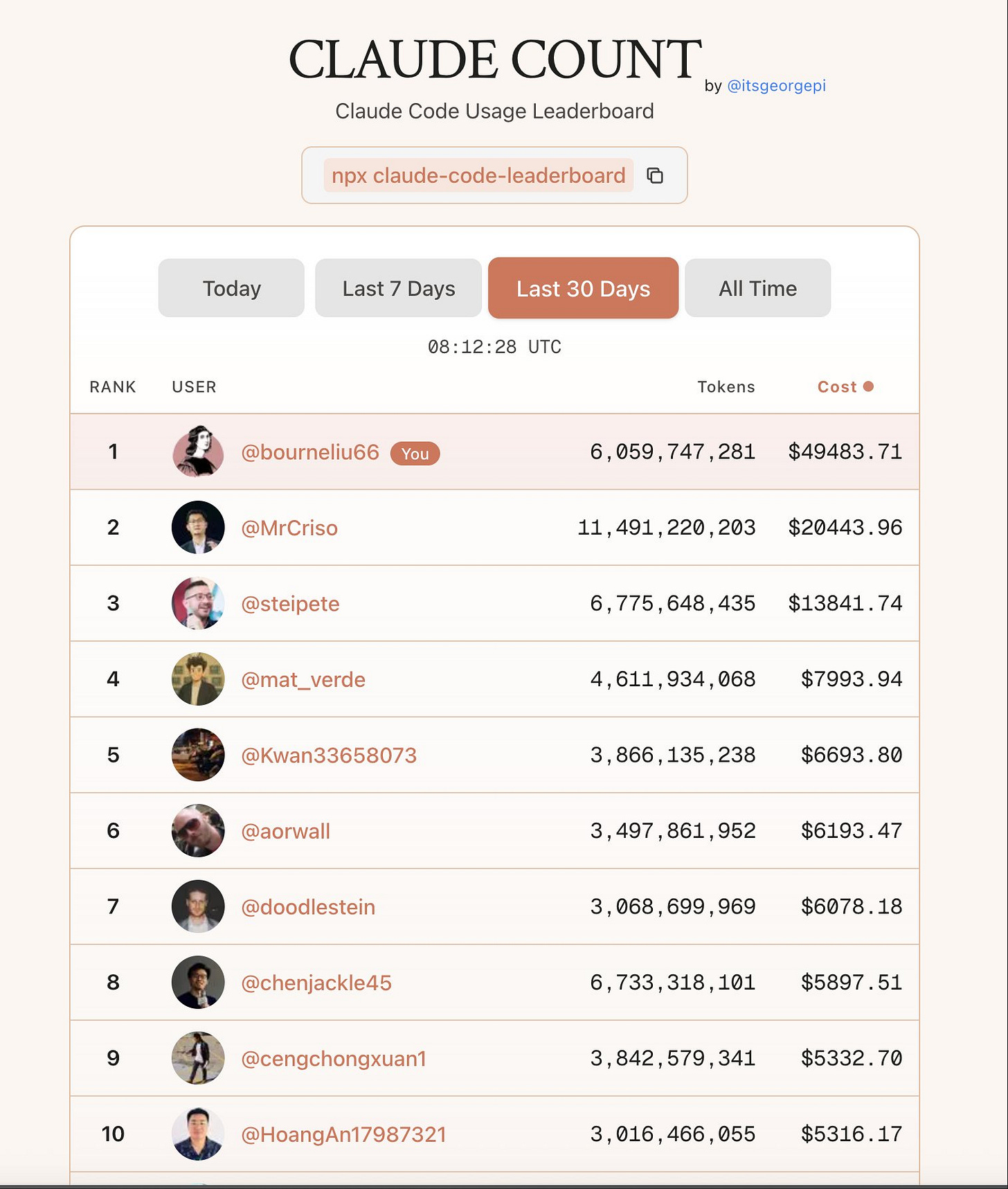

Three months ago, engineers at Anthropic discovered something strange: an account burning through Claude’s computational resources at an impossible rate, 24/7. The announcement came with a striking revelation: one user, on a $200 monthly plan, had consumed $50,000 worth of model usage—a global record.

The culprit is a Beijing-based programmer named Liu Xiaopai. As an entrepreneur who’s been building products for over two decades, first working for a big company and now on his own, he used Claude Code ceaselessly to make money: building a dozen AI products while he slept, selling them to users in places (mostly the West) he’d never visit. Some at Anthropic called him exploitative, and people on Reddit discussed this crazy phenomenon with mixed reactions. Liu Xiaopai didn’t find the whole thing embarrassing; instead, he bragged about it.

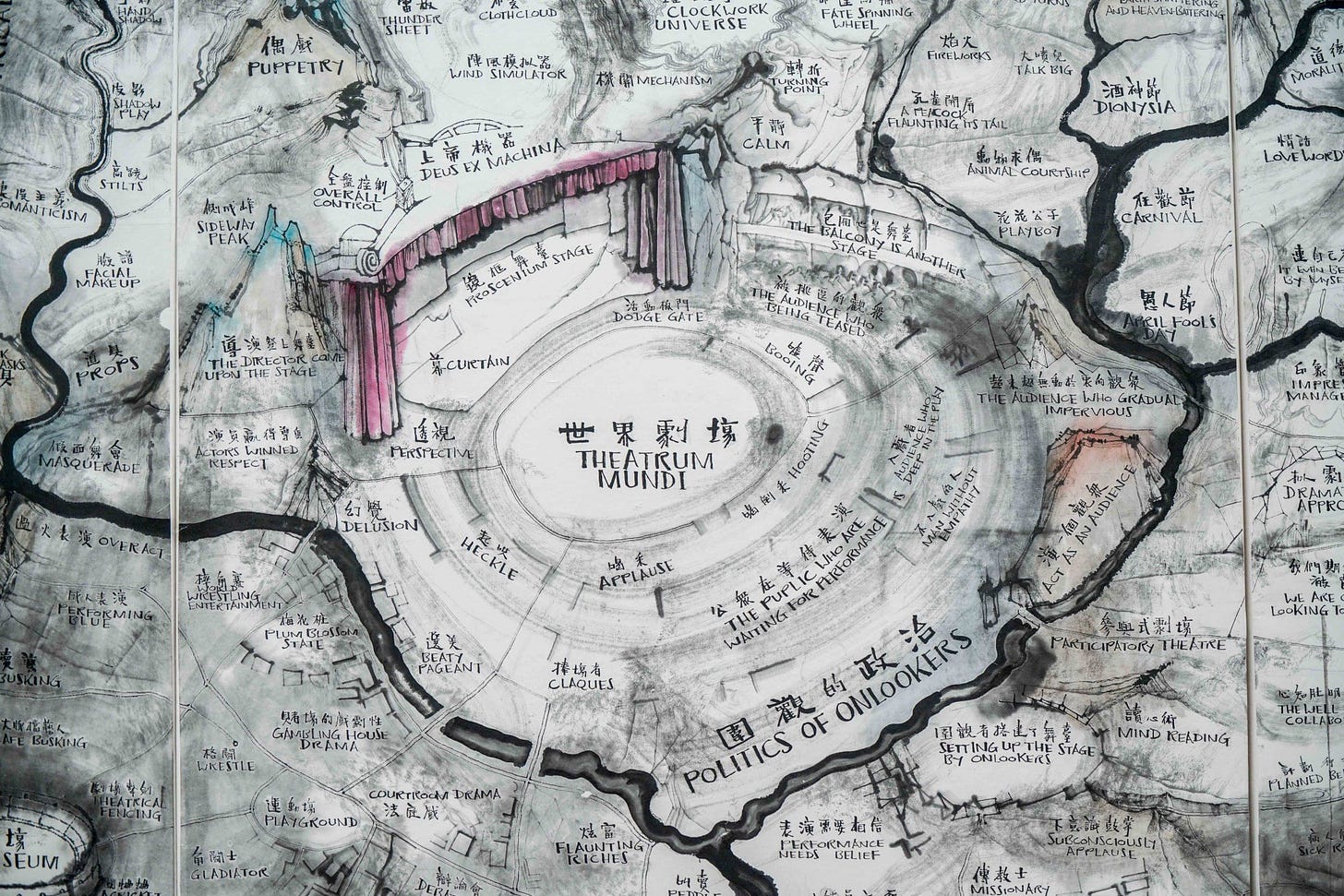

I found this story captivating, as it seems to reveal a certain zeitgeist about Chinese engineers. To be specific, this extreme grinding energy. China’s tech world operates as a different kind of arena entirely, the most notable features being its resource constraints and intense competition, thus breeding such strange cases.

Start with the fundamentals of China’s tech reality: its SaaS market remains stunted, a fraction of Silicon Valley’s scale. The culture of paying for software never quite took root. For Chinese AI founders, the environment is far harsher than what their American peers face: no deep-pocketed a16z-style venture capitalists fueling a risk-taking ecosystem, yet a fiercely involuted market where few users are willing to pay. There are no $100 million offers from Zuck, only relentless competition and shrinking margins. On top of that, export controls have throttled access to advanced NVIDIA chips, forcing Chinese models to train on far leaner compute budgets.

An unspoken consensus has crystallized among Chinese AI entrepreneurs, captured perfectly in the article “The Cold Reality for Chinese AI Start-ups“ translated by

: Launch products overseas. Develop in secret, profit quietly. Launching domestically means losing money. If truly unfeasible, relocate to Singapore or elsewhere. Think the company Manus here.If you work in AI, China is simply a more brutal game. Yet such brutality breeds innovation in unexpected ways.

China’s tech world has already exported methodologies that reshape Silicon Valley: Meta’s Reels still chases TikTok’s more mature algorithm. WeChat and Meituan’s super-apps showed Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg what application boundaries could become. Top AI labs import China’s “996” work culture, that dark gift where survival requires sacrificing more, working more, shipping faster.

Innovation lives on trial and error, iteration, and correction. When China’s market accelerates this cycle manifold, a harsh environment becomes an evolutionary advantage. If China operates as a more brutal arena, a more selective crucible, then who stands out from the forging process?

The answer is probably someone like Liu Xiaopai. Through a mix of vibe coding and hands-on management of more than a dozen successful AI products sold overseas, he clears around a million dollars a year—pure margin. In Beijing, that’s the income of a legend. (For comparison: the city’s average disposable income for the first three quarters of 2025 was ¥67,206—about $10,000.) Among the exhausted dachang (大厂, meaning “big factory,” as Chinese tech workers often tease themselves to be factory laborers) coders chained to their desks, Liu Xiaopai is the exception.

Liu speaks almost no English. Never studied abroad, never worked overseas, has no plans to leave Beijing. He’s not the hyper-elite Chinese AI talent that captures American imagination—he graduated from Chongqing University, a solid engineering school that would barely register in Stanford’s sphere. Language barriers mean he ignores Silicon Valley hype cycles, focusing instead on grounded concerns: improving products with proven use cases, quietly profiting, and winning. He is among a cohort Silicon Valley rarely recognizes: experience-rich super vibe coders who never left China, yet build software that competes globally.

Yet Liu Xiaopai’s business model draws deeply from Paul Graham and from the Silicon Valley playbook. His user-finding methodology is YC-coded: start with a small and nimble team, target boring verticals, use AI to replace specialized tasks, profit from arbitrage most people would ignore, and make something people want.1

What Liu discovered about Claude Code—what only someone in his position could discover—emerged directly from resource scarcity and ferocious competition in China. And only in China, with countless programmers fighting over scraps compared to American abundance, could a coder learn to extract maximum value from every computational second and every penny they paid. You might say, but Claude banned Chinese users. How did he use Claude Code? Liu Xiaopai will surprise you with many ways to maneuver such a ban. We chatted briefly on this matter, and Xiaopai is not concerned.

My immature assessment is that if any phenomenon is “happening in China first, might happen in Silicon Valley later,” super-individuals like Liu Xiaopai could be one. By using Claude, he escaped the hamster wheel as a regular tech worker and gained meaningful agency and income. The Liu Xiaopai phenomenon has been contingous in China. And that might be noteworthy.

I chatted with Xiaopai a month ago and found his rawness and utilitarianism very representative. Below, we talked about:

The User of Claude Code Who Burned 50k with $200

Reaction to the Anthropic Ban on China

How Liu Xiaopai Automates the Entire Product Lifecycle

From Corporate Cogs to Independent Creators, Liu Xiaopai’s Vibe Coding Incubator

Vertical Applications: The Overlooked Goldmine in Specialized Tools

Holistic Thinking vs. Technical Fetishism: What Actually Drives Success

Learning from Pieter Levels and Paul Graham

Being the AI-Age Super-Individual

From Scarcity to Idealism

To note:

At the end of the article, I’ve attached three AI applications he built that gained traction in the West and made him a lot of money, which he’s very proud of. I’m not endorsing his work and have no intention of promoting his products. I also have zero monetary connection with him and wrote this piece out of curiosity and admiration for China-based super vibe coders like him.

The User of Claude Code Who Burned 50k with 200$

Afra: Many on the Chinese internet call you “the world’s most prolific Claude user”. As a developer using Claude Code, you consumed so many tokens within Anthropic’s allowed limits that the company had to issue a global policy adjustment affecting every user a few months ago. How does one burn through $50,000 worth of tokens in a month? What were you building with them?????

Liu Xiaopai: Yes, you could call me “one of the most proficient Claude users.” I’m simply a product developer using it for everything my company needs to build software for global markets.

Coding is just one part of the work—there’s also technical research, algorithm optimization, operations, and more. My business model is straightforward: create software products from my own ideas, then monetize them with users in developed countries. The two most critical components are coding and operations.

That $50,000 monthly burn rate is no longer achievable. Anthropic has imposed three successive usage caps, each more restrictive than the last. Now I can consume roughly $20,000 per month, while new users max out around $6,000-$7,000. How did I reach those levels? It doesn’t require arrays of computers—you simply need to keep Claude running continuously on your tasks. It’s not particularly difficult.

Before those three rounds of caps—in July, August, and late September—things were different. In July, it was relatively simple. An ordinary Claude user who coded from morning to night, maintaining constant interaction, could easily spend over $10,000 monthly. If you engaged with Claude all day on requirements and code generation, you’d consume $400+ daily. So if you could keep Claude working while you slept, reaching $1,000+ per day was straightforward.

Afra: I’m curious, do you believe token consumption correlates with output? Why use dollars spent as your metric?

Liu Xiaopai: There’s definitely a positive correlation. AI-focused entrepreneurs like us now closely track token consumption. I’ve heard that some Silicon Valley startups essentially evaluate candidates on just two factors—resumes have become obsolete artifacts of the previous era. They look at: how many Claude tokens you’ve consumed, and your GitHub commit history.2

To your question about correlation with output—yes, absolutely, though not linearly. If you consume 10x the tokens of someone else, your output might only be 2x theirs, not 10x. Many people think you should conserve token resources. But what’s the cost of conserving computational resources? It means you, as a human, consume more time. Under Claude Code’s initial policies, I didn’t care about conserving computational resources—I cared about conserving my time and energy, freeing myself for more creative work. At least in early July, Claude Code’s token limits were essentially unlimited, so my entire usage philosophy aligned with what it permitted. I didn’t care how much electricity or how many tokens it consumed. I only cared about saving my time, energy, and attention.

Reaction to the Anthropic Ban on China

Afra: Returning to Anthropic, they ban all Chinese users recently. What’s your perspective? You’re still using Claude, so you must have workarounds. What are they?

Liu Xiaopai: First, your description isn’t quite accurate. Anthropic, from inception to present, has never been permitted in China. Not for a single day. They may have recently intensified enforcement, but this isn’t a new policy—it’s always existed.

To work around this ban, I have a UK company, so I registered my account through it. My account appears British, pays with a UK card, uses UK IP addresses. Others employ various tactics—VPNs, borrowing others’ cards... Access barriers will continue rising because this has always been their policy. So fundamentally, you’re engaged in an adversarial game: they devise methods to block you, you devise methods to access, this continues indefinitely, and access barriers escalate.

Afra: What’s your view on the ban? Do you think you’ll eventually stop using Claude Code?

Liu Xiaopai: Probably soon. Right now, domestic Chinese programming models are rapidly closing the gap. Zhipu’s GLM-4.6 now outperforms Claude Opus 4. Zhipu launched around March this year, so we’re only about six months behind. Even at the beginning of this year, I wouldn’t have dared imagine domestic Chinese programming models lagging the world’s best by only six months. Back then, I thought we were two years behind.

Afra: But you’re still using Claude Code. Do you feel like an “AI immigrant”? Having to route through the UK specifically—doesn’t that seem cumbersome?

Liu Xiaopai: Not really that burdensome. When you’ve never used it before and first attempt to access these American products, it’s somewhat complicated. But once you’ve figured it out, there’s no complication.

How Liu Xiaopai Automates the Entire Product Lifecycle

Afra: Was there a specific moment when you realized Claude had fundamentally transformed your working methods?

Liu Xiaopai: Too many to count. Building software products for overseas markets—programming actually represents only a small fraction.

Look at any normal internet company in China: engineers comprise just 20-30%. What about the remaining 70%? They are design, product management, testing, operations, user growth—these roles require substantial human resources, and nearly all follow standardized operating procedures (SOPs).

After using AI to solve the programming component, I faced a larger challenge: how to automate all the work with standardized processes? After entering July, I spent more time with Claude Code on non-programming tasks. Here’s a simple use case that was previously impossible: I need to launch a new product, which requires naming it and registering a website domain. Let’s say I build the product Manus, with the domain Manus.ai. Sounds simple—but this having a product name and domain means many steps, and each step was hard to automate before. You’d brainstorm names, then manually check domain availability one by one; it’s too time-consuming. How about using AI to generate 10,000 viable domains and instantly determine which are available for registration? Thus, determine the product name?

I would begin by writing product requirements documentation. Then I’d list all the competitors, noting how each differs from mine and what features I want to emphasize. I write an extensive description, and then have Claude synthesize this information to auto-generate 10,000 appropriate domains and query their registration status. Then I can go to sleep. Five or six hours later, the results arrive. I automate many SOPs like this.

Afra: Do you consider yourself the world’s most skilled Claude Code user? Do you know others who use Claude Code at your level?

Liu Xiaopai: I know quite a few independent developers in China. I even run an incubator—really just a shared office space. People like me in Beijing form a tight-knit circle, and most people maintain low profiles. I’m already among the most outspoken; many others are flying low. They predominantly build AIGC consumer applications, exclusively for overseas users. Why? Because Chinese users don’t pay, so we need to target international markets. This existed before AI coding. The barrier was simply higher then. Today, with vibe coding, an individual can create complex applications indistinguishable from products built by major tech companies.

Afra: when AI coding began became a thing, many people believed 2-3 person teams could build billion-dollar companies, create unicorns. These “super individuals”—you must already be one, right?

Liu Xiaopai: That’s my goal for next year. My current daily revenue is actually just a few thousand dollars, translating to annual revenue of around $1 million. If we’re talking valuation, I’m probably worth around $10 million. But I haven’t taken funding. If I sought investment, my current scale could probably command a $10-20 million valuation.

So what I’m working toward now is transitioning from building a matrix of small products to challenging myself with something larger. Perhaps it’ll emerge in Q1 next year. I’ve seen many such cases—though rare domestically, more common overseas. Midjourney started with just a few people, Cursor initially had only a dozen or so. That’s my goal for next year. Domestically, overall, people haven’t reached that stage yet. My $1 million+ annual revenue is already quite good in China. Most people might be at $30-50k monthly.

From Corporate Cogs to Independent Creators, Liu Xiaopai’s Vibe Coding Incubator

Afra: What backgrounds do these quietly prospering Chinese vibe coders and small teams share? You yourself quit a big tech company to start your own business. Before that, you worked as a product manager at Cheetah Mobile for ten years. Are there many people like you?

Liu Xiaopai: My observation - former product managers from internet giants like Tencent probably constitute over half of my community. I’ve identified several trends:

First, Chinese tech giants grow increasingly large and bureaucratic, with astronomical internal communication costs. A product manager wanting to build something must convince their team, convince their boss, convince their boss’s boss, then initiate projects, navigate various review processes—months might pass without any actual work beginning. After project approval comes the large team writing requirements documents, conducting reviews, designing—another several months before anything materializes.

But product managers inherently understand these processes. Previously, the only thing they didn’t understand was writing code. Today, AI vibe coding has filled that gap. So experienced product managers, especially those from major tech companies, represent the demographic most likely to become AI-era winners. When they have ideas now, they don’t need to beg anyone—they build it themselves in a week. If it sells, excellent. If not, no matter—it only took a week, so they’ll try something else next week.

Here’s an example: someone in my incubator came from Tencent, previously at Tencent Sports, then WeChat Pay. He resigned last November, already fed up with big tech bureaucracy. Back then, Claude Sonnet didn’t exist yet, but Cursor did, so he began teaching himself vibe coding. By April-May this year, he’d built his first product—an English-language app for Chinese Bazi fortune-telling. Initially earning $100+ monthly. Now, having built additional products, he’s reaching $1,000 in income daily.

Afra: You now run an incubator specifically nurturing these opportunistic, execution-capable big tech product managers?

Liu Xiaopai: It’s a byproduct, though calling it an incubator isn’t quite accurate. Essentially, after I resigned to start my own venture, I rented too large an office—you can hear the echo when I speak—and felt somewhat lonely, so I created a co-working space. Those attracted here are naturally people wanting to do what I do. They pay me 1,000+ RMB monthly for desk space. Among them, some kindred spirits think “this is good, let’s collaborate,” so I find ways to help them—providing resources or pathways—while taking a small equity stake, perhaps 10%.

Afra: I think you could become China’s Pieter Levels, the godfather of independent development. You could teach online courses like him.

Liu Xiaopai: I already teach courses as a side business—earning over 10 million RMB annually.

Vertical Applications: The Overlooked Goldmine in Specialized Tools

Afra: What kinds of products are these Chinese vibe coders developing?

Liu Xiaopai: Let me describe this ecosystem. They’re predominantly building AIGC consumer applications, but here’s the key—they start from extremely specific user needs. To achieve tens of thousands in monthly revenue, you absolutely don’t need to build large products.

Take video as an example. Text-to-video or image-to-video generation is rapidly maturing—Veo, Sora 2.0, and similar models possess formidable capabilities. But there’s still enormous application-layer opportunities here: building specialized tools for professional users atop these model capabilities.

Ordinary people face a critical problem using Veo directly: they simply cannot produce quality videos because they can’t articulate effective prompts. Some people build tools that let average users avoid “gacha randomness” (抽卡)—though the backend calls Veo, users can generate decent-quality videos. Or consider this: when users see potentially AI-generated videos on TikTok, you provide a tool enabling direct replication, simply swapping in their own likeness. If you can deliver these capabilities, users will pay—because without your tool, they cannot achieve these results directly with Veo or Sora 2.

The image-generation domain offers even more opportunities. China has vast numbers of cross-border e-commerce sellers with straightforward needs: AI-generated product images they can use directly in their online storefronts. That’s the need. Build such a tool, and they’ll certainly pay.

Run the numbers: imagine I’m a 400-person e-commerce company with 50 designers. If your tool enables me to reduce those 50 designers to 10, I’m saving 40 salaries monthly. My willingness to pay becomes extremely strong.

What tools do they need? Highly specialized ones. Example: a clothing seller has photographed their model wearing a garment in two or three shots, but it’s insufficient. Same model, same clothing, but I only have 3 original images—I need 300 variations: different angles, different poses, different backgrounds, all undetectable as AI-generated. Someone develops precisely this kind of micro-tool. Both sides win: buyers save costs, developers earn money.

From a major tech company’s perspective—ByteDance, Google—they cannot even detect these opportunities. But for individual developers or small teams, this market demand is substantial.

Holistic Thinking vs. Technical Fetishism: What Actually Drives Success

Afra: You observe these relatively invisible Chinese vibe coders pursuing market needs that even major tech companies cannot see. What advantages do they have?

Liu Xiaopai: Regarding advantages: first, these Chinese vibe coders possess sharp market sense. They can see a holistic picture.

Consider WeChat, which employs many product managers. Many product managers work on a single feature for years—like “Double Tap.” If such a product manager leaves to start a venture, they’ll struggle to sustain themselves. A former subordinate of mine went to JD.com. For JD.com‘s search functionality, their department employs over a dozen product managers focused solely on search optimization. For JD, that’s fine—given their scale, improving search by one percentage point pays for itself. But if they only know how to do that one thing, leaving the company makes self-sufficiency extremely difficult.

There’s another factor: Chinese big tech overemphasizes technology. People constantly say “your product lacks a technical moat.” But in the real world, you don’t need technical moats to win. Some people develop an excessive reverence for technology at big companies because those companies have their own hierarchies—you’re T6, they’re T8, T9 (they are Alibaba’s ranks), forming a contempt chain. But whether you’re T6, T7, T8, or T9, none of you are making money.

So, making money with AI apps doesn’t depend on technology; it depends on perceiving user needs. Many people do leave big tech. They might not be very high-P, or they’re high-P but fortunate enough to see the complete picture of a small business, possessing commercial thinking. Such people tend to be more genuine.

Whether there are many or few is a relative concept—compared to what? Within all of ByteDance, such people might be uncommon. But in my circle—those earning $50k+ monthly through just vibe coding—I probably know a dozen or so.

Learning from Pieter Levels and Paul Graham

Afra: Who are your heros?

Liu Xiaopai: I greatly admire Pieter Levels. About 10 years ago, he began independent development, building SaaS products solo, now generates millions in annual revenue. And he achieved this in the pre-AI era.

I’ve been doing such independent development for a decade. I’ve always enjoyed tinkering. My happiest moments come when I create something people find delightful, something they consider excellent enough to recommend.

Building software is my form of entertainment. I’ve been building products for two decades. My largest user base resides overseas. By revenue: first America, second Germany, third Japan, fourth probably the UK. Correlates with national consumption capacity. I receive daily user feedback—some curse me, some thank me. I’ve somewhat lost count now, which is actually a problem. I have one or two dozen revenue-generating products. These dozen-plus product websites collectively receive around 200,000 daily visits. Previously, at peak, we hit 400,000 daily visits. But these are visiting users—not every visitor registers, not every registrant pays, so paying users is far fewer. I haven’t checked the total, but I generate roughly 200 new paid subscriptions daily.

Afra: Which book has influenced you most profoundly?

Liu Xiaopai: My past two decades of building software have been profoundly inspired by Paul Graham’s Hackers & Painters. The core thesis—PG argues that the software business is the world’s best business because its marginal cost approaches zero. And software creators, like painters, are engaged in creation, not construction labor. These concepts have deeply influenced me. Additionally, I enjoy Tools of Titans and Tribe of Mentors by Tim Ferriss.

Tim Ferriss’s own success methodology is quite impressive—his key to victory involves surrounding himself with the smartest people, observing how they work, understanding their beliefs, then emulating them, studying these elements, and thus achieving success himself.

Afra: It seems Hackers & Painters was pivotal for your trajectory. I’d suggest reading Paul Graham’s updated blog posts, since Hackers & Painters essentially compiles his old essays. I’ve always wondered why he hasn’t published a new edition.

Liu Xiaopai: I definitely need to read his recent writings.

Afra: But I notice your thinking methodologies actually derive from Silicon Valley? Just with Chinese characteristics.

Liu Xiaopai: Silicon Valley’s greatest influence on me is YC. YC’s entire entrepreneurial methodology centers on making things people want. And YC has always believed small teams can accomplish great things.

China’s mainstream entrepreneurial approach is what I called micro-innovation with intense competition—continuously refining already mature products. For instance, 10 years ago when ride-sharing emerged, Didi was followed by a swarm of competitors. Want to do group buying? The Hundred Regiment War (百团大战)begins. Want to do bike-sharing? Numerous bike-sharing companies materialize. These people definitely aren’t YC believers. YC believers encourage small teams building relatively independent, more unique products, not super-apps.

Afra: Perhaps your core principle is uniqueness. What you’re doing is very YC. For instance, YC’s recent AI batches build things very much like yours—highly vertical, targeting specific application scenarios. Though you’ve never participated in YC, I think you’re a spiritual YC entrepreneur.

Being the AI-Age Super-Individual

Afra: You’ve said your goal for next year is to become an AI-enhanced super-individual, building a highly valued company. What do you envision for yourself in five years?

Liu Xiaopai: I’m working toward that goal. I currently have a concern: I’m actually more famous than my products, but going forward, I hope my products become more famous than me.

Afra: What’s your ultimate aspiration—your ideal product?

Liu Xiaopai: What I’m about to build, what I want to build next year, might look like this: it will satisfy an old need, but within that old need will be new technology, and its interaction paradigm should transform. For example: Photoshop. Image editing has existed for perhaps 30 years. Now AI has arrived, AI can generate images—do people need Photoshop or not? I’ve discovered they do. Because even at companies most proficient with AI, their designers still use Photoshop for image modifications. So there must be a tooling opportunity—how do we enable traditional designers to harness AI capabilities across all their domains? Nobody has built this yet. People are attempting it, but nobody’s succeeded. This is what I want to build.

Afra: What’s your favorite AI product? How do you use it?

Liu Xiaopai: Definitely Claude. My usage of Claude probably exceeds even WeChat. Because Claude embodies a philosophy that many non-technical people don’t know: Claude Code has no interface, only a terminal. But consider: 40 years ago, computers had no interfaces either. We interacted through command lines. Controlling everything on a computer required only a terminal, not interfaces at all.

Today, I control everything on my computer with just Claude. It’s even more intelligent than old terminals. So for me, Claude isn’t remotely just a coding tool—it’s my tool for operating everything on my computer, my entry point for computer usage. Recently at Alibaba’s Apsara Conference, didn’t Wu Yongming say AI will become the operating system? AI is the operating system. I’m already living in that reality.

Afra: If given the opportunity to work and start a company in Silicon Valley, would you accept?

Liu Xiaopai: Absolutely not. I’ve had such opportunities before and declined. Because all my friends are in Beijing. I don’t have close friends in Silicon Valley. Going there means rebuilding friendships from scratch. I don’t yearn for Silicon Valley.

From Scarcity to Idealism

Afra: Do you think Chinese entrepreneurs like you will increasingly resemble American counterparts, becoming more idealistic?

Liu Xiaopai: The Chinese people haven’t been well-fed for very long—genuinely haven’t been well-fed—so they lack the privilege, haven’t developed the habit, of pursuing somewhat ethereal ventures.

After several years of accumulation, I feel my belly is definitely well-fed, so I could pursue more idealistic endeavors. I think it’s also about establishing a healthy relationship with money. Many Chinese people don’t lack money, yet they maintain a starving mentality because they haven’t established healthy relationships with money. I’ve resolved this, have begun establishing a healthier relationship with money. But Western-born founders’ idealism and healthy money relationships are often innate. I only achieved this transformation after accumulating wealth, realizing I have enough for several lifetimes, then converting from scarcity mindset. So Westerners possess this “innately”(生而知之); we acquire it “through learning.” (学而知之).

I found the following on Liu Xiaopai’s WeChat public account. He is, of course, a well-known AI influencer in China.

Raphael AI - https://raphael.app

An AI image generation product with a distinctive feature: users can generate unlimited, decent-quality images without logging in. Of course, if you’re willing to pay for VIP membership, you gain access to premium features.

This product became incredibly popular. Open Douyin/YouTube/TikTok or any social media platform worldwide and search “Raphael AI”—you’ll find countless videos with tens of thousands of likes.

AnyVoice - https://anyvoice.net

A voice cloning product. With just 3 seconds of original audio, it can clone remarkably realistic voices.

Fast3D - https://fast3d.io

An exceptionally fast text-to-3D and image-to-3D conversion product. All code generated using Claude Code. No registration required, no login needed—one-click conversion of images or text into 3D models.

Just to note here that I’m not endorsing the YC motto—in fact, I think it’s one of the most problematic ones, as it encouraged many tech founders to be lazy and path-dependent on today’s infested attention economy.

I am not sure about this and would love to verify.

Loved this

As an attorney, I think he may have a case against Anthropic for breach of contract when they unilaterally cut him off. He should look into filing a lawsuit and protecting his rights as a consumer - and by that extent - the rights of all consumers.