Progress in Chinese Urbanism

A conversation about Datong, urban renewal, and finding the future in the past

From Jeff:

China is a complex place, particularly for those of us who don’t live there (i.e. me). There’s a lot that doesn’t make sense as an outside observer, even on topics like urbanism and technology, where I have more than a little expertise. So, in an effort to understand an important part of the world in a much deeper way (and have all of y’all benefit in the process), I sat down with the writer behind Concurrent (my new favorite publication on China and Silicon Valley) — Afra Wang.

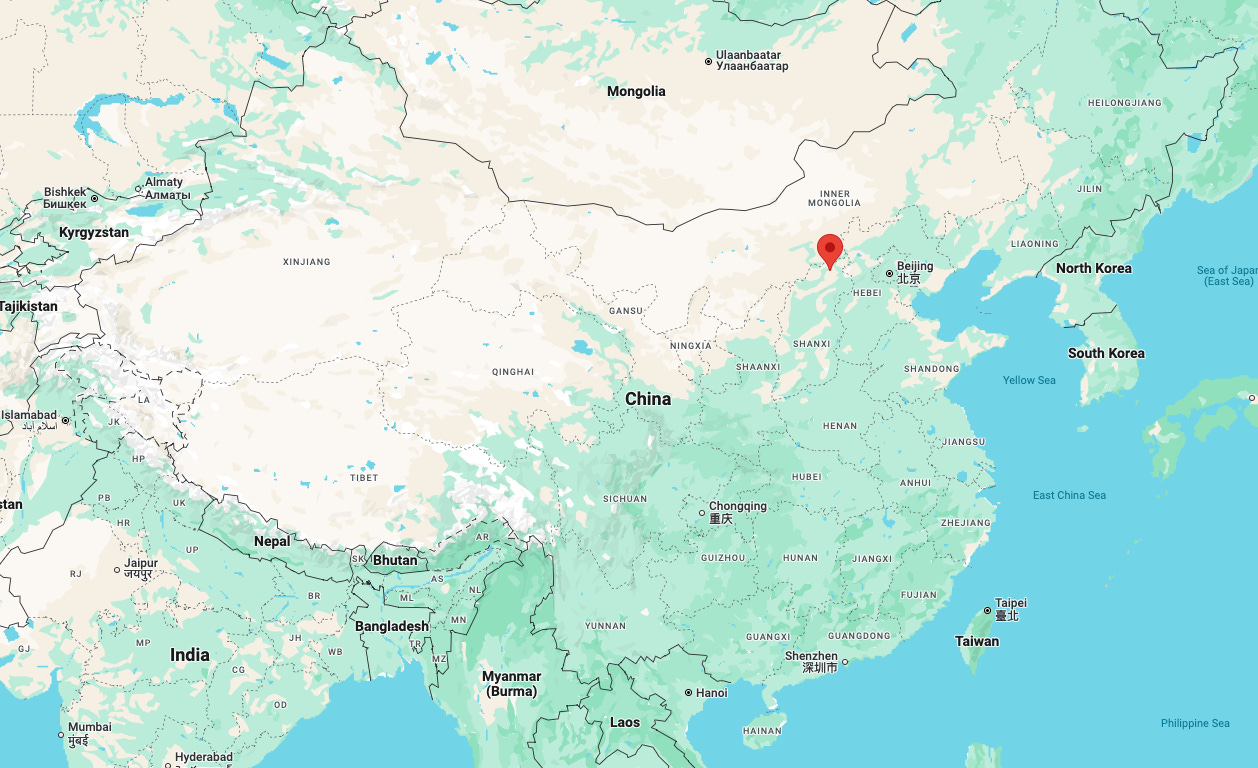

Afra walked me through the story of Datong, a city to the West of Beijing in Northern China. On one level, it’s one city’s tale of ancient history, industrialization, and urban redevelopment. On another, it’s a larger commentary about what pride of place means in modern China and how progress as an ideal is all about going back to former glory.

From Afra:

Before Jeff (the writer behind Urban Proxima) proposed our conversation about Chinese urbanism, I had never considered Datong through an urbanist lens. But as I've reflected these past few days, I've come to believe it's one of China's most underestimated cities—a case study that deserves attention amid China's rapid urbanization and the CCP's narrative of rejuvenation and progress.

Datong's story is inseparable from its former mayor, Geng Yanbo—a figure embodying the hybrid of Elon Musk-style cut-throat efficiency and traditional Confucian bureaucrat that characterizes thousands of local CCP officials transforming China from within. When Geng was promoted to the provincial capital, thousands of citizens literally knelt in the streets, begging him not to leave. He had fundamentally altered Datong's trajectory, but left behind 13 billion RMB in municipal debt—a quintessentially Chinese story of transformation and its costs.

I first visited Datong as a child, when it was grimy and heavily polluted. Returning this year, I found something extraordinary: a place seamlessly combining heavy industry with restored ancient architecture, and it had become Beijing’s “backyard” (I wrote about my experience in this travelogue piece, “China In Flux”). As I told Jeff, it's like a mystical fusion of Kyoto and the Rust Belt—a combination that captures the essence of contemporary Chinese urbanism.

Datong might offer American urbanists crucial lessons:

How can a seemingly "hopeless" ordinary city enhance its competitiveness through urban development? How do we find the right pace when both too-fast and too-slow development profoundly impact real people's lives? And how does China's urbanization miracle manifest in a small city like Datong that the West barely notices?

Datong’s Invisibility Paradox

Jeff: I know a little bit about Datong from your China in Flux post, but maybe you can say more? For example, there's a certain view that New Yorkers have about what it means to be a New Yorker, and then there's a certain view the rest of America has about what it means to be a New Yorker. How does that work for Datong?

Afra: That's such a fascinating question because Datong is, in many ways, both insignificant and deeply significant. The reason I care about it is personal—I grew up in Shanxi Province and visited Datong as a child, but I hadn't been back for twenty years. When I returned last winter, I witnessed this absolutely stunning, almost zero-to-one transformation.

What struck me is how Datong exists in this curious space of visibility. From a Western perspective, or really from any perspective outside of China, it's completely invisible. You've heard of Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hangzhou, Beijing, but never Datong. Even within discussions of Shanxi Province, people talk about coal mining towns in general, but Datong doesn't even register in that landscape. It's the insignificance of insignificance.

But here's the paradox: Datong carries enormous historical weight. It was a crucial link on the Silk Road and served as China’s capital of the Northern Wei dynasty.

The Northern Wei were an ethnic minority that conquered a significant portion of China and established what they claimed was a glorious dynasty. Yet this history—this period when ethnic minorities held power—has been gradually either erased or carefully recontextualized within Han-centric narratives.

So yes, Datong had historical glory, but it was glory from the past that’s achieved under non-Han rule, which complicates how that legacy gets remembered and celebrated today.

Jeff: I'm going to ask this question in a very American way. You mentioned that normal people in Datong look back fondly on this (non-Han) historical legacy. Do people in Datong identify with being non-Han? My understanding is that, politically, modern-day China really leans in on the primacy of the Han ethnic identity.

Afra: That's exactly the tension at the heart of Datong's identity confusion. It's a contradiction—why does the city so romanticize this non-Han past while everyone today is expected to celebrate ethnic integration under Han dominance?

If you visit Datong Museum, you'll see this narrative tension played out across three floors. From the third floor down to the first, everything displayed celebrates the Northern Wei dynasty and the Tuoba Xianbei ethnic group. You see artifacts depicting people who weren't primarily agrarian—they were traders, hunters, nomads whose economic life centered around horses and camels. The tomb discoveries reveal beautiful burial sites of non-Han noble families from thousands of years ago, with artifacts showing people hunting, trading, and living this mobile lifestyle.

But then, as you go deeper into the exhibits, you encounter this awkward, almost artificial language about "ethnic integration" and how, after many years of Northern Wei rule, this ethnic fusion somehow parallels present-day China's approach to ethnic unity. It's clear the local curators carry a political mission—they want to educate visitors about this past, but only in a very particular way that ultimately leads back to the narrative fortress of glorious Chinese reunification.

The reality is that today's residents of Datong—many likely descendants of Han and ethnic minority fusion—all identify as Chinese without question. But when they talk about making Datong attractive again, making it great again, reducing its dependence on coal mining, they invoke this glorious history. They say, "Datong is competitive because it was once a capital city, because it had cultural significance, because it was a crucial Silk Road link."

This is when Datong's culture merchants, history workers, and government officials try to package a story that makes their city competitive among hundreds of Chinese cities. The ethnic complexity gets smoothed over in the service of contemporary economic goals.

Jeff: It sounds like there’s a desire from local officials to tell this story about what makes Datong unique and noteworthy, but they then have to also resolve the tension that this creates with the prevailing political orthodoxy.

Afra: Exactly, though I'd emphasize that this wasn't some calculated strategy. This ethnic fusion happened organically over thousands of years. It was, in many ways, a beautiful integration. But here's the bind: if you're a local history teller today, the Northern Wei period represents the most significant part of Datong's past. You want to write about it in detail, to really explore its richness, but eventually, that last paragraph has to circle back to the “correct” narrative. As a local historian, your performance metrics at the government level require you to be aligned with Han Chinese orthodoxy.

China's blood boy in the Reform and Opening era

Jeff: Yeah, I’m hearing that there wasn't some content strategist in the 80s (at the start of the Reform and Opening of China) who came up with this. The narrative evolved organically over time.

Afra: Datong's economic story is essentially a millennium-long decline punctuated by one brutal irony. After the Northern Wei Dynasty collapsed, the empire's center shifted south, and Datong, this former imperial capital, became increasingly irrelevant. I will fast-forward Datong's story.

Then comes Deng Xiaoping's reform era, and Datong's geology becomes its curse. The city sits on enormous coal reserves: high-quality coal just meters below the surface. You literally dig and find coal everywhere. This transformed Datong and all of Shanxi Province into what I think of as China's "blood boy," constantly drained to fuel the country's industrial miracle.

When Deng announced his famous reform mantra—"let some people get rich first" (让一部分人先富起来)—the implication was clear: others would stay poor. Datong represented that sacrifice. While Beijing transformed from an imperial city to a gleaming metropolis, Tianjin became an international port city to welcome the increasing export demands, Datong remained a polluted mining town for decades.

The dynamic was ruthless but simple: China's northern industrial bases needed power, and Datong had abundant blood to transfuse. Even today, the biggest employers in Datong are still state-owned coal mines. So you'd watch Beijing's skyline transform while Datong choked on coal dust, a resource colony funding someone else's modernization.

That's the context that makes Geng Yanbo's transformation so remarkable. He looked at this dynamic and said: we're going to flip the script entirely.

Jeff: That makes sense. There's extensive commentary in Latin American development literature about local economies founded on resource extraction failing to create durable economic bases. They peter along until the resources dry up, and then the mining town just dies.

Afra: But Datong's tragedy is different. Some Latin American industrial towns didn't exist before industrialization; immigrants came, extracted resources, and then left. Datong has been home to millions of people for millennia, people with deep ancestral ties to this place. It was once the northern capital of China.

The heartbreak is that this historically glorious city became purely a resource provider for decades. I remember my first childhood visit—my father wanted to show me these incredible temples and historical sites dating back 1,000 to 1,500 years. But these treasures were scattered throughout what felt like Kyoto mixed with West Virginia’s Rust Belt.

I was small, holding my dad's hand, when this gust of wind hit me carrying garbage and coal dust that just overwhelmed me. My father said that after three days in Datong, you'd blow your nose and the water would turn black from coal debris. The residents developed this bitter, self-mocking saying: "Garbage is cleared by the wind, sewage removed by evaporation, illegal vendors are never caught, and the city's appearance is never improved." Everyone—from children to the elderly—knew these lines. They'd laugh, but with this resigned shrug: "This is our cursed fate, and we don't know what to do." The city felt trapped in poverty and pollution.

Jeff: You said something really important. This shift to resource extraction happened in a city that's been continuously inhabited for over a thousand years. That breaks my sense of scale; the oldest city in the U.S. is maybe New York at 400 years if you count Dutch colonization. With that kind of historical continuity, does it change people's willingness to move? Americans, especially in previous generations, would just pick up and move across the country for better opportunities. I imagine there are much stronger ties to place in China, especially in places like Datong.

Afra: People from the Shanxi Province have this reputation for not liking to move, and there are geographic reasons for that. Shanxi is essentially a plateau, elevated above most other Chinese provinces. When you take the high-speed rail there, snack packages will pop due to the elevation change.

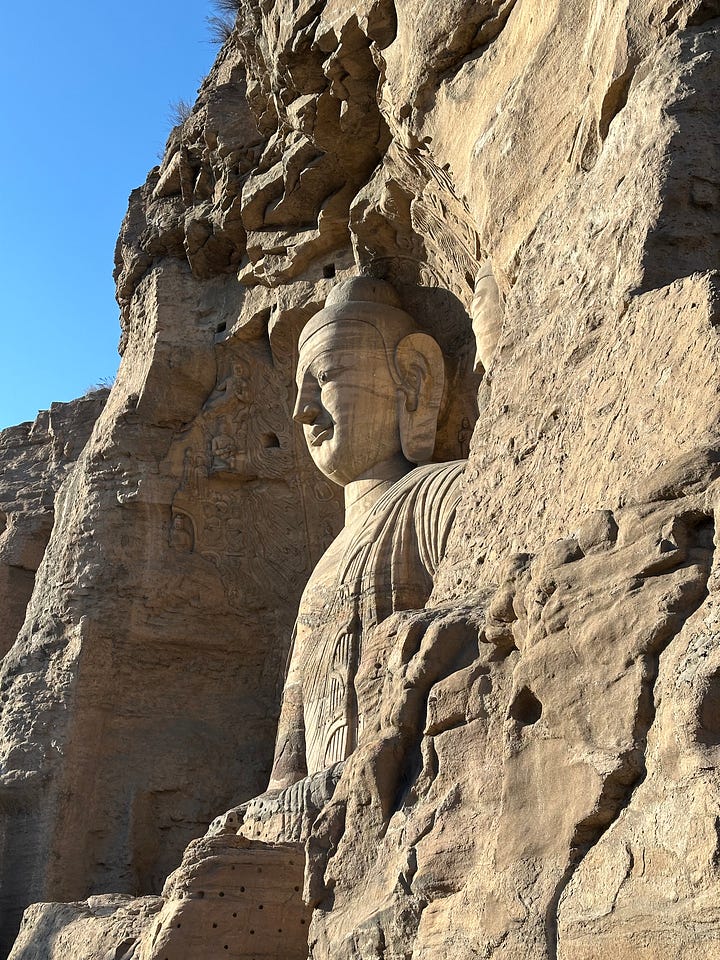

Historically, Northern Shanxi's communication networks ran inland toward Central Asia through the northern routes of the Silk Road, rather than toward China's more central regions or coastal areas. This meant that unlike other parts of China, Datong wasn't devastated by wars. Many historical buildings and architectural sites remain relatively well-preserved compared to other Chinese cities. So yes, it really is like Kyoto meets Rust Belt—you'll see the Yungang Grottoes, these magnificent Buddhist cave complexes dating to the fifth and sixth centuries, with 51,000 Buddhist statues within a carved area of 18,000 square meters. But walk ten minutes and you'll encounter massive coal mining operations, with trucks transporting coal while the debris erodes those very same Buddha statues. That was the reality through the '90s, '80s, and well into the early 2010s.

Meet China's Elon Musk of urban renewal

Jeff: Listening to you describe Datong, it sounds like there are three different versions of the city layered over each other: the really old historical stuff, the parts built during the coal mining era, and the recent post-urban renewal construction. Is it like a patchwork where you're walking down a block and pass an old monastery, new building, and then something from the coal mining era? Or is it more that entire neighborhoods or sections of the city are distinct?

Afra: When I was a child visiting Datong, I mostly experienced the ironic contrast between the most valuable Chinese Buddhist grottoes and these massive trucks carrying coal, with pollution destroying the city around these ancient treasures.

But today is far more surreal because Datong has been completely rebuilt. Historically, during the Ming and Qing dynasties, Datong had a beautiful old town with city walls and a moat. Over time, it became run-down—parts were demolished, sections of the city wall disappeared, while others were preserved.

What you see now is a complete reconstruction of this old town on the original site. This is where Mayor Geng becomes central to the story. He actually found the original city blueprints from the Ming and Qing dynasties—blueprints for the city walls that are 500 to 600 years old—and recreated much of the city based on these historical plans.

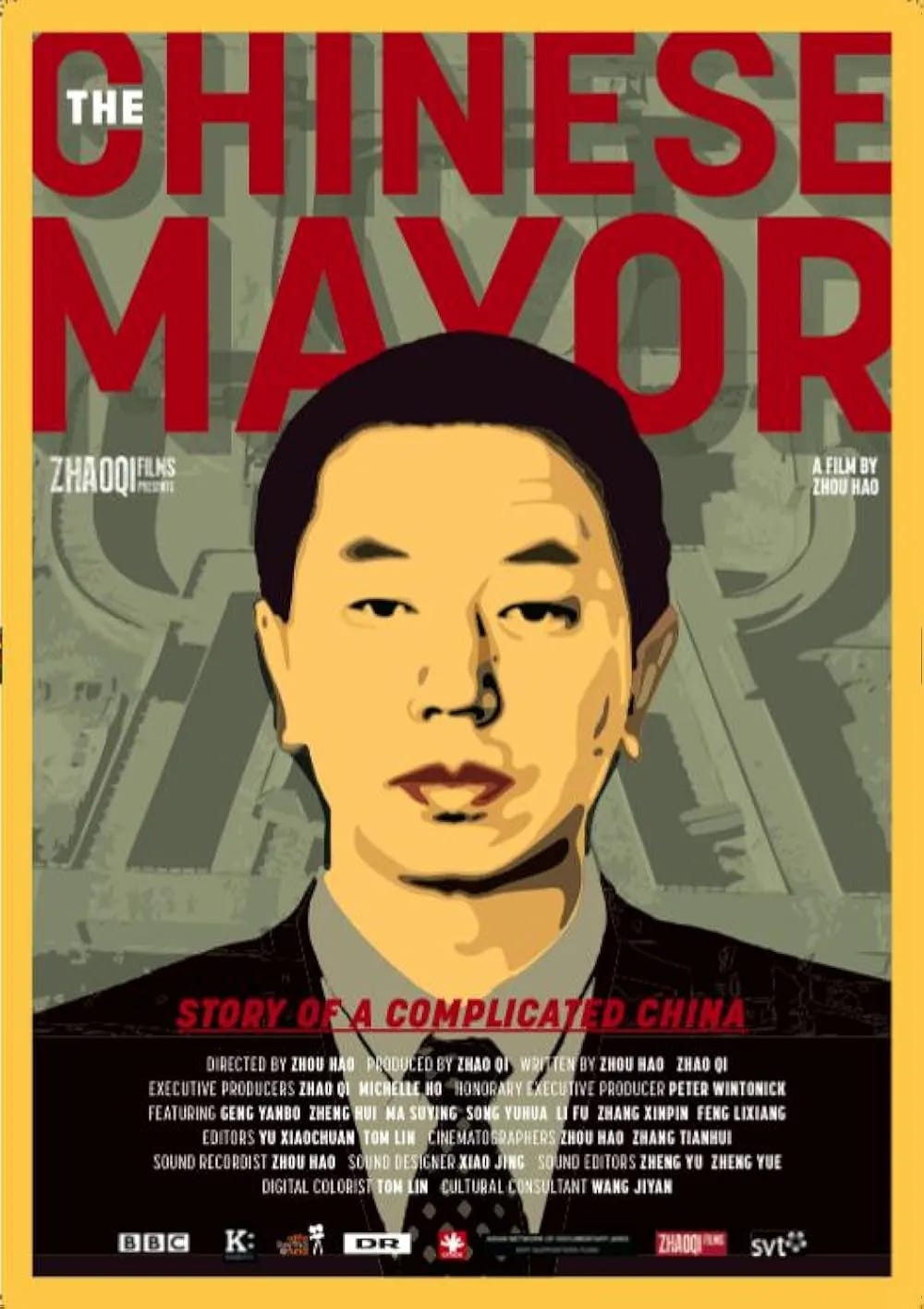

Mayor Geng is this fascinating, iconic figure who was featured in the BBC documentary "The Chinese Mayor," which won a Sundance. He's a local Shanxi native whose determination was to transform the regional economy from coal dependence into tourism.

His political track record started in an even smaller city, Lingshi 灵石, where he rebuilt the Wang Family Compound—a beautiful complex belonging to a wealthy Ming Dynasty merchant. That restoration project was enormously successful, turning Lingshi into a tourist destination and giving the city its own renaissance.

When Mayor Geng saw this formula worked, he thought, "I'm going to do something bigger." He got promoted to Datong specifically because of his accomplishments. His approach was to find the most valuable historical sites he could restore in Datong, which turned out to be the old town itself: a massive project. We're talking about an old town so large that walking from one side to the other takes at least an hour. It's designed in that classic Chinese urban planning style—square, centrally organized.

Jeff: Right, is this one of these situations in which the old city — with its borders defined by a wall — has just become a neighborhood as the modern version of the city continued growing out around it?

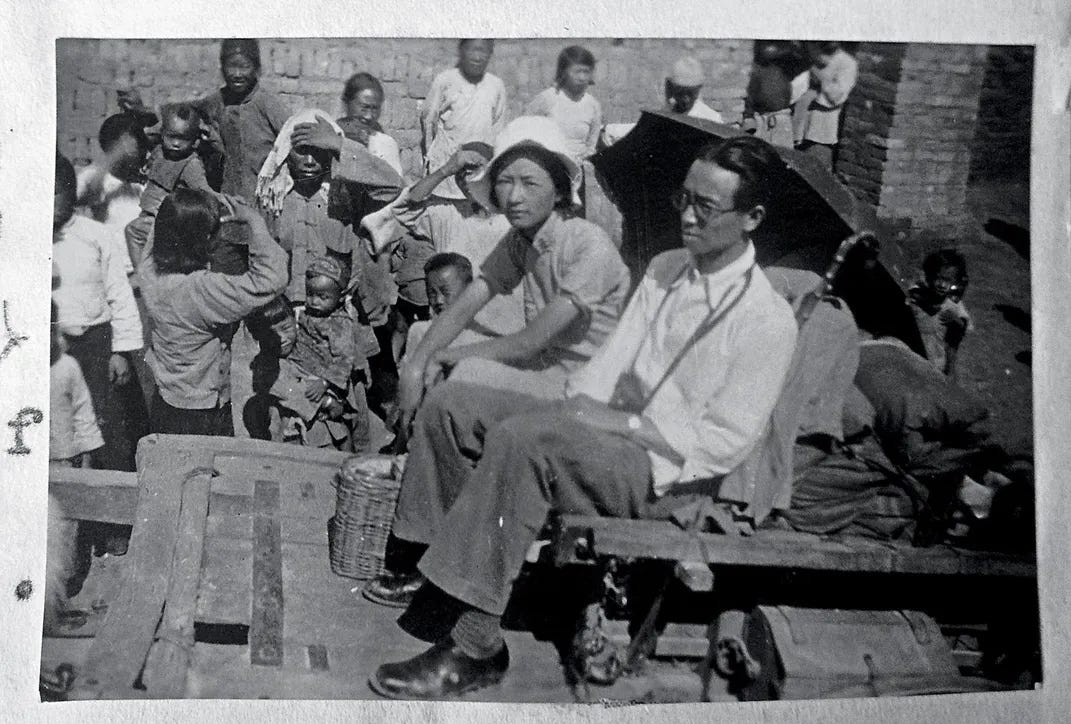

Afra: Exactly, just like Beijing. Mayor Geng was a devoted follower of Liang Sicheng 梁思成, the "father of modern Chinese architecture." Liang was the son of famed revolutionary Liang Qichao 梁启超 and studied at the University of Pennsylvania's architecture department in the 1920s. In the 1950s, Liang Sicheng famously proposed a "One Axis, Two Cities" 一轴双城 plan to Beijing's city planners. Rather than demolishing the entire old city, he suggested preserving Beijing's old town—the hutongs, the Forbidden City, and all historical architecture—while building a modern city adjacent to it. People could travel between the historical and modern areas via subway or car.

However, Beijing's city planners rejected this proposal and demolished the beautifully preserved city walls, which became one of the biggest regrets in Chinese urban planning history. Mayor Geng wondered, "Why can't I apply this 'One Axis, Two Cities' concept to today's Datong?" He essentially became Liang Sicheng's most devoted apprentice, even though they never met and were separated by several decades.

Geng is the Elon Musk of Chinese mayors: ambitious, bold, betting on moonshots, and a tireless worker who would sleep on construction sites. He directly engaged with technicians and electricians when bureaucracy slowed things down and bypassed reporting lines entirely. He'd approach workers and say, "Tell me what's blocking you. I'll remove those obstacles and let all the corrupt municipal officials know I'm not here to mess around—I'm here to rebuild this city." This approach reminds me of many Silicon Valley founders. It's hard to imagine an American mayor doing the same.

I highly recommend the BBC documentary "The Chinese Mayor"—which won an award at Sundance in 2015. You'll see Geng constantly demanding accountability, sometimes harshly, firing people on-site when they couldn't meet his standards. Urban legends tell of him calling meetings at 6 AM after making the call at 2 AM, then firing people who didn't show up because they thought he was joking. This relentless work ethic is why he was eventually promoted to mayor of Taiyuan, the provincial capital, where he's implementing the exact same restoration approach.

Jeff: This is giving me big Silicon Valley founder energy.

Afra: Oh, yes, 100% founder mode, which is very Silicon Valley coded. But understanding Mayor Geng also requires understanding the Confucian dimensions of Chinese governance and what history truly means to officials in the CCP. He strongly identifies as a Shi (仕)—a scholar-bureaucrat carrying enormous civic responsibility and historical weight. He sees his role as leading a cultural renaissance, embodying what China calls rejuvenation. He felt compelled to pursue local rejuvenation, helping Datong return to its glorious historical periods.

He reads Confucian texts, practices Buddhism, and creates calligraphy. I saw his poems written in his calligraphy, carved in wood as couplets at the entrances of restored ancient temples in Datong (a common way for Chinese bureaucrats to leave their historical legacy). As a Confucian official, a Shi, his responsibilities transcend time: he must care for today's min (民), the people, while bearing responsibility for historical Datong, honoring past generations and serving future ones.

I remember the BBC documentary where Mayor Geng broke down crying from the pressure. Sobbing, he said, "This is the last chance for Datong. If Datong misses this opportunity, it won't get another one in a thousand years."

Chinese bureaucrats embody both old and new traditions. They might study Marxism, modern Western political science, Xi Jinping thoughts, but to truly understand Chinese politics, you must go back to the 2,200-year-old Confucian texts.

Jeff: I'm having a couple of immediate reactions to some of these stories, especially talking about Liang Sicheng. If he was trained in the States in the 1920s, this would have been just a little after men like Robert Moses got out of school. And he, Liang, strikes me as that kind of last-century modernist setting out to play SimCity with an entire urban environment.

In the U.S., this legacy is something we’ve grappled with a lot over the last century, but has there been any similar tension in China? In Datong, did anybody have a negative reaction to the redevelopment plan that Geng pursued? Reactions like the redevelopment being too big of a change or the plan not fully considering the impact on those affected?

Afra: I can't speak for the entire city, but what I observed is that when Mayor Geng came to power in Datong in 2008, China was experiencing such radical transformations that people had developed an extraordinarily high tolerance for rapid, large-scale change. It wasn't seen as particularly significant to quickly develop multiple massive projects simultaneously.

More crucially, Datong was—and I use this term because residents themselves used it—literally a shithole. That self-deprecating saying I mentioned earlier wasn't just dark humor; it reflected genuine despair about their physical environment. Having visited the city in its polluted state, I understood how dire conditions were. The city felt it had nothing to lose.

When someone arrives promising to rebuild the entire urban fabric, everyone embraces it. Simultaneously, hundreds of Chinese cities were undergoing similar renaissance/improvement processes. Mayor Geng's vision aligned perfectly with widespread expectations of urban progress.

This occurred during China's period of 10-11% GDP growth. That explosive economic expansion fundamentally expanded everyone's conception of what was possible. The collective response was, "Yes, let's do this."

Mayor Geng represents an extreme case of comprehensive city planning and rebuilding. However, at the same time, Mayor Geng didn't completely rebuild Datong from scratch, but instead spent enormous time and money on restoring the ancient city.

That said, while the overall mood in Datong was one of support, there were people displaced and some historic neighborhoods erased. The coverage of Mayor Geng's work (e.g., in The Chinese Mayor documentary) shows resistance from residents being relocated. However, those voices were often drowned out or dismissed in the name of progress. Unlike the U.S., China hasn't had a widespread cultural reckoning with the long-term impacts of this kind of urban planning—yet. There's still a strong belief in state-led transformation as beneficial overall, even if it comes with short-term human costs.

Urban renewal figures like Robert Moses, looking at China's context, would probably think, "This is a much more accommodating canvas to work with." High modernist approaches—Corbusier-style separation of workplace and residential districts, the belief that human intervention can reshape anything—remain highly revered in China.

Jeff: Given the circles I run in, I look askance at the way Corbusier thought about urbanism and I think men like Robert Moses did terrible things. Admittedly, though, I’m coming from a U.S. perspective, so I’m highly skeptical of the “give one guy all the power” approach. But it’s interesting to hear folks in a different context having a very different default opinion on these things.

So let me ask another question. When you're describing Mayor Geng embarking on this campaign of urban renewal, of recreating this historical quarter in the city to spur tourism, I — as an American — immediately have several assumptions. I'm like, well, he’s (Mayor Geng) trying to increase tourism, which will increase revenue from sales taxes, hotel taxes, and so on. And, ultimately, like, sometime in the next 10 or 20 years, someone will write a white paper to decide whether or not it made the city more fiscally solvent and, on that basis decide whether the redevelopment was a success (and, of course, cultural commentators will have things to say along the way).

But is that actually how Geng, as a Chinese Mayor, is thinking about it? What are his OKRs, or incentives? How do normal people actually think about whether the redevelopment is “working”?

Afra: The transformation was just undeniable, you know? Many people compare China over the past 40 years to the United States in the first half of the 20th century—you see a town suddenly become a metropolis. You watch the Empire State Building go up. The progress is so visible and tangible that you don't really question whether the city has improved because you can see it just did. Everything looks newer, more magnificent. Retail prospers, bridges and highways and train stations get built. It's going well because it's so stunning and transformative.

Datong has indeed successfully transformed itself from a pure resource provider—this grimy coal town—into a cultural tourism destination. People in Beijing now call Datong their "backyard garden." It's both slightly derogatory and flattering. Because Datong is beautiful, cheap, has great weather, and people can actually consume there. But Datong was absolutely not a backyard garden 15 or 20 years ago. If you went there, your nostrils would be blocked with coal dust. It was not a garden at all.

The fact that it's now referred to as a backyard garden suggests Datong has transformed its role relative to rich regions like Beijing. You can take the high-speed train there in less than two hours, and it's become a weekend destination for wealthy Beijing residents. That was unthinkable 15 years ago—Datong wasn't even in consumers' mental map as a place where you'd think, “I can spend money there, eat and shop and tour around." It was never a thing, and now it is.

Progress in China: walking forward by turning back

Jeff: Ok, so beyond whatever the tax receipts look like, there's a felt sense of Datong achieving some cultural significance. That cues up some questions about other aspects of municipal governance in China. When I listen to you talking about Datong, I start assuming things like Mayor Geng pursuing redevelopment as a way to increase revenue…which is maybe not the case here. But I realize I’m also imagining a Mayor acting under electoral political constraints, which, I suppose, is also incorrect, right? Geng would have been appointed by some higher-level party official?

Afra: Yeah, exactly. That's how municipal appointments work—promotion is very meritocracy-based and growth-based. Mayor Geng had done really well in Lingshi, another city I mentioned, so he had this reputation as someone who could successfully identify the cultural significance of places and transform their economic models into something more tourism-oriented and attractive. He had this brilliant track record.

After he transformed Datong, he was instantly promoted to Taiyuan, the capital city of Shanxi province, to become mayor there—that's a significant promotion. And he did the exact same thing in Taiyuan. He rebuilt Taiyuan's old town, which is almost hilarious. I visited that old town too—very empty but absolutely gorgeous.

Jeff: And the incentives come from the top down? My understanding was that provincial governors were given GDP targets from Beijing and everything was evaluated on that basis.

Afra: Absolutely, yeah, GDP figures and other metrics matter. But okay, I constantly feel like people need to read more Confucius to understand 2025 Chinese politics. I see Mayor Geng as a very typical Confucian official. The reason is that he carries this sense of civic responsibility for cultural renaissance—almost like this rejuvenation that China constantly talks about, right? The rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. I think Mayor Geng was carrying out this localized rejuvenation for his city.

As a Confucian scholar-official, he carries a lot of historical weight to restore the city back to what it was during its glorious period. I remember watching The Chinese Mayor—Mayor Geng was crying in front of the camera because of the enormous pressure he was enduring while pushing this whole urban renewal project forward. He was sobbing, saying, "This is the last chance for Datong." He was basically saying Datong deserved to be saved and deserved to be seen, and he had this responsibility not to let Datong miss this one chance.

He quotes Confucian texts constantly, he reads classical scripts, he's Buddhist. The way he interacts with people, with other officials, is very Confucian-coded to me—the way he understands his role vis-à-vis the state, the court, other people. In Confucian ideology, your position in society is assigned, and I think he strongly self-identifies as a Confucian scholar-official who needs to take very strong civic responsibility and carry historical weight. He's responsible not just for today's Datong, but for historical Datong. He almost feels this ancestral calling.

Jeff: I think I'm having a moment of cognitive dissonance. There's a very American part of my psychology that's reacting negatively to this hierarchical Confucianism. But at the same time, there's a part that wishes our elected officials were just better—specifically at taking responsibility for not just a community as it exists today, but also a community in perpetuity. A major problem in American electoral politics is politicians thinking in two, four, or six-year terms and operating only in those time horizons.

Afra: Yeah, exactly.

Jeff: And there's something else I keep hearing you mention. Maybe this is implicit, but it sounds like in China, progress is conceived of as a way to go back.

Afra: You got it exactly right. Chinese progress is constantly propelled by restoring certain periods of Chinese history. It's almost the standard template for any Chinese progress project.

Jeff: And in urban redevelopment, this shows up literally in the recreation of historic city centers.

Afra: Exactly. When you walk through Datong's city wall—this massive archway—you see people ice skating on the frozen moat, and then you step through that arch and suddenly this "New Old Town" presents itself. You literally feel like you've walked into history, like this place has been unchanged for millennia. But the crazy thing is, that wall was built ten years ago. Most of those "ancient" buildings were built ten years ago. Yet you have this incredible sense of continuity.

Jeff: It's such an interesting juxtaposition. I spent time in Lisbon once—another very old city where they preserve historic districts, often for tourism. It's cool, but sometimes feels like a museum exhibit. Tired, aged in a certain way. But when you describe Datong's renewal, it sounds like someone trying to drink from the fountain of youth—an attempt to return to youthful vigor and be what it was at its peak.

Afra: That's a perfect metaphor. Datong represents this development model where you restore the past, but here's what's fascinating: because the economy was so destroyed by coal mining, certain kinds of modernity never arrived. Modernization and restoration happened simultaneously. You see high-speed rail being built, people buying cars, experiencing this beautiful modernity, but concurrently with the Old Town restoration.

What I wrote in my piece: "Datong resembles many Chinese cities that have laid-back development—simultaneously awaiting modernity's arrival while longing for a return to China's past."

That's the feeling—Datong is trying to erase the bitter past, the coal dust and pollution, and say: "this is what we were during the Ming and Qing dynasties, during the glorious Northern Wei period. And now we're back."

Great piece - thanks for sharing!

I enjoyed reading this article and I can't wait for us to cover Datong. our first City in Shanxi is Xinzhou, so we have to wait for maybe season 2. Xinzhou will be week beginning 31 December