China in Flux

A travelogue of my 1-month wanderings through China

The phrase "Chinese diaspora" has never sat right with me. Its official translation—"离散" (lí sàn)—compresses too much melancholy into two characters: departure and dispersion. It indicates withered roots and perpetual exile.

My reality feels more defined: code-switching between the U.S. and China demands less effort. The distance is technological, not existential.

Like every return to China, I bifurcate the moment my feet touch Shanghai. The first state: a researcher's consciousness, clinical and questioning, trying to make sense of contemporary China. The second is a cellular homecoming, where my body remembers everything. My American self dissolves. The floating uncertainties of immigrant angst evaporate. When a bowl of congee and a cup of milk tea arrive within 25 minutes of ordering at one-fifth the U.S. cost, my mind calculates the impossible Chinese math on labor and raw material prices, but gravity feels right again.

I often read accounts from people who offer definitive insights or “truths” about China based on brief stays and conversations with taxi drivers. Yet even natives must journey across provinces to grasp fragments of this country. China's magnitude defies easy understanding. We can only offer it glances: each region reveals new realities, and every cross-province trip emphasizes how fleeting any single perspective becomes.

So here is my travelogue, my gaze on China.

Cao Fei

The first night in Shanghai I won the double lottery: I found Museum of Art Pudong(MAP) opens till 9pm, and Cao Fei’s solo exhibition Tidal Flux 潮汐宙合 was still on.

Cao Fei is a contemporary Chinese artist I've been dying to see. Her works speak directly to that researcher consciousness in me, forming a narrative that charts how technology molds China's reality. Standing in MAP, with Bund’s colonial architecture visible across the Huangpu River and Lujiazui's glowing skyline, I couldn't have asked for a more fitting backdrop to visit her work.

The exhibition's name "Tidal Flux" mirrors this theme, showing contemporary Chinese reality as an endless tide where waves of the surreal crash against the viewer, one after another. Among the many pieces in this expansive exhibition, three works left an indelible impression on me, each revealing a different facet of China's technological transformation and how it reshaped Chinese society, industry, and human connection. The three pieces are "Asia One," "11.11," and the "Hongxia Project."

"Asia One," the first installation and short drama, catapults viewers into a near-future that has already begun materializing. This drama unfolds in JD Group's high-tech logistics center. Only two human employees remain, working alongside a robotic assistant as they become entangled in a strange love triangle. The piece feels like watching a modern Chinese version of 2001: A Space Odyssey, except where Kubrick gave us the desolate expanse of space, Cao Fei offers the vast emptiness of an e-commerce warehouse—both spaces equally capable of inducing claustrophobic dread. And in place of HAL 9000, we find a humanoid robot that wouldn't look out of place at the Las Vegas CES.

Moving through the maze-like installations, I next encountered "11.11," Cao Fei's hypnotic documentary on China's Black Friday. Taken out of context, it might appear to be propaganda showcasing industrial achievements—the vibe eerily similar to CCTV's documentary Great Power's Heavy Equipment 大国重器. Yet between shots of impressive machinery, Cao Fei's lens lingers on warehouse workers dispatching countless packages across China. The juxtaposition simultaneously celebrates and questions China's e-commerce miracle.Cao Fei’s China is deeply late-capitalistic: she captures the backstage pageantry of JD.com before and during “11.11”, when the entire nation's fingers collectively tap-tap-tap on smartphone screens, resulting supply chain and logistics tsunami. Handling this chaos is both the film's subject and its subtext.

What makes viewing "11.11" particularly poignant is the recognition that the system it documents—already mind-boggling in its scale and efficiency when filmed in 2018—appears almost quaint now as the logistics infrastructure has evolved into an even bigger and more effective behemoth. And it hits uncomfortably close to home.

Since my grandmother discovered Douyin (Tiktok’s China counterpart), she has also discovered online shopping. Pinduoduo, a shopping platform with massive discounts, has become one of her daily must-visit apps. She spends an unhealthy amount of time scrolling on her Xiaomi smartphone, using Douyin and Pinduoduo. From 1-yuan kitchen supplies to 15-yuan smart bulbs that connect with Xiao Ai (小爱同学, China's Alexa), impossibly inexpensive products arrive at her doorsteps within 0-3 days. Those packages often arrive bundled in protective cocoons of cardboard and bubble wrap. The economics and speed of China’s e-commerce defy comprehension. I remain baffled at how this pricing and speed is possible—the packaging alone should cost more than some of these items.

Not to single out my grandmother as the only digital consumer in the family—we've all succumbed. On the third night of Chinese New Year, with Beijing temporarily hollowed of its migrant workforce, I found myself alone, standing in front of the automated package station of my parents' apartment complex. The fluorescent-blue LEDs cast an eerie glow across what resembled an architectural model of a miniature city: cardboard towers stacked floor-to-ceiling.

The warehouse door yielded to my Taobao QR code with a mechanical sigh. Inside, thousands of packages awaited their owners in silence. I scanned my order QR code and somewhere in the room, my parcels began beeping noise. I searched, simultaneously regretting my consumerism while enjoying the dopamine rush of treasure hunting and unboxing.

My contradictory mental state on China’s online shopping—half critique, half surrender—resonates deeply with Cao Fei's “11.11”: overwhelming, absurd, scary, yet reluctant awe at the sheer scale of this empire built on algorithms and human backs alike.

The subsequent Cao Fei exhibition ventures further into the realm of the uncanny China, becoming even more quintessentially Cao Fei. One notable work, the "Hongxia Project", or “HX”, is aptly summarized in an Observer review as "an attempt to formulate an epic, polyphonic narrative that preserves local memories of a controversial chapter in China's recent history while simultaneously exploring the past and imagining alternative stories." The installation transports viewers into a 1950s movie theater in suburban East Beijing—one of many workers' cinemas bearing the dreamlike imprint of the socialist era. In the early days of the People's Republic, this district rapidly transformed into a nexus of archaic electronic industry when numerous military factories—including Plants 718, 738, and 774—were constructed with Soviet and Eastern European assistance.

The socialist industrial aesthetic evokes both the Red Coast Base from "The Three-Body Problem" and the state-owned coal mine in Shanxi where my grandfather worked his entire life and where I was born—an energy conglomerate around which an entire town organized its existence. By the time of my birth, these state enterprises had already begun their decline, yet my formative years from age 1 to 7 were steeped in the distinctive culture of socialist industry until my parents relocated us to Taiyuan, the provincial capital Shanxi. The sense of progress was ubiquitous; no one spoke in dialect; everyone existed within a complex web of relationships determined by their position within the organizational structure; children attended "workers' offspring elementary schools"; and cinemas like Hongxia represent a golden age of socialist China. The Hongxia project seems to extract time itself, leaving China suspended between the cinnabar-hued past and the present of JD's automated warehouses.

On the third floor of the Museum of Art Pudong lies a remarkable expansive space where your gaze can traverse the Huangpu River to behold the Bund's colonial-era legacy—the "Exhibition of Ten Thousand Nations"—on the Puxi side, while also taking in Lujiazui's iconic "Three-Piece Suite" in Pudong: those cyberpunk skyscrapers occasionally glimpsed on TikTok, glowing with fluorescent light and wrapped in LED screens. Though the sky lacks the thousands of drones forming dazzling shapes as seen in TikTok videos, everything about Shanghai is in-your-face glamour.

Shanghai

My connection with Shanghai emerged nearly a decade into my American life, after years of visiting the city as nothing more than a passing tourist. True fascination bloomed only when I fell under the spell of Ang Lee's "Lust, Caution" and read about Shanghai's colonial history. This rediscovery felt like seeing, as an adult, that the overlooked porcelain in your childhood home was actually a priceless antique vase. Each return to China now includes a deliberate detour through Shanghai—the city has become my benchmark, an upper bound of Chinese reality against which everything else is measured. Mid-January 2025 found Shanghai dry and cold, its streets filled with people caught in that peculiar pre-Lunar New Year limbo, simultaneously tense and expectant.

In April 2021, work brought me to Shanghai for three months—the longest I'd stayed in any Chinese city since entering adulthood. Shanghai existed then in a peculiar bubble of "zero cases" while COVID ravaged the rest of the world. After two weeks of quarantine in a hotel on the outskirts of Pudong, I was in Shanghai's early summer.

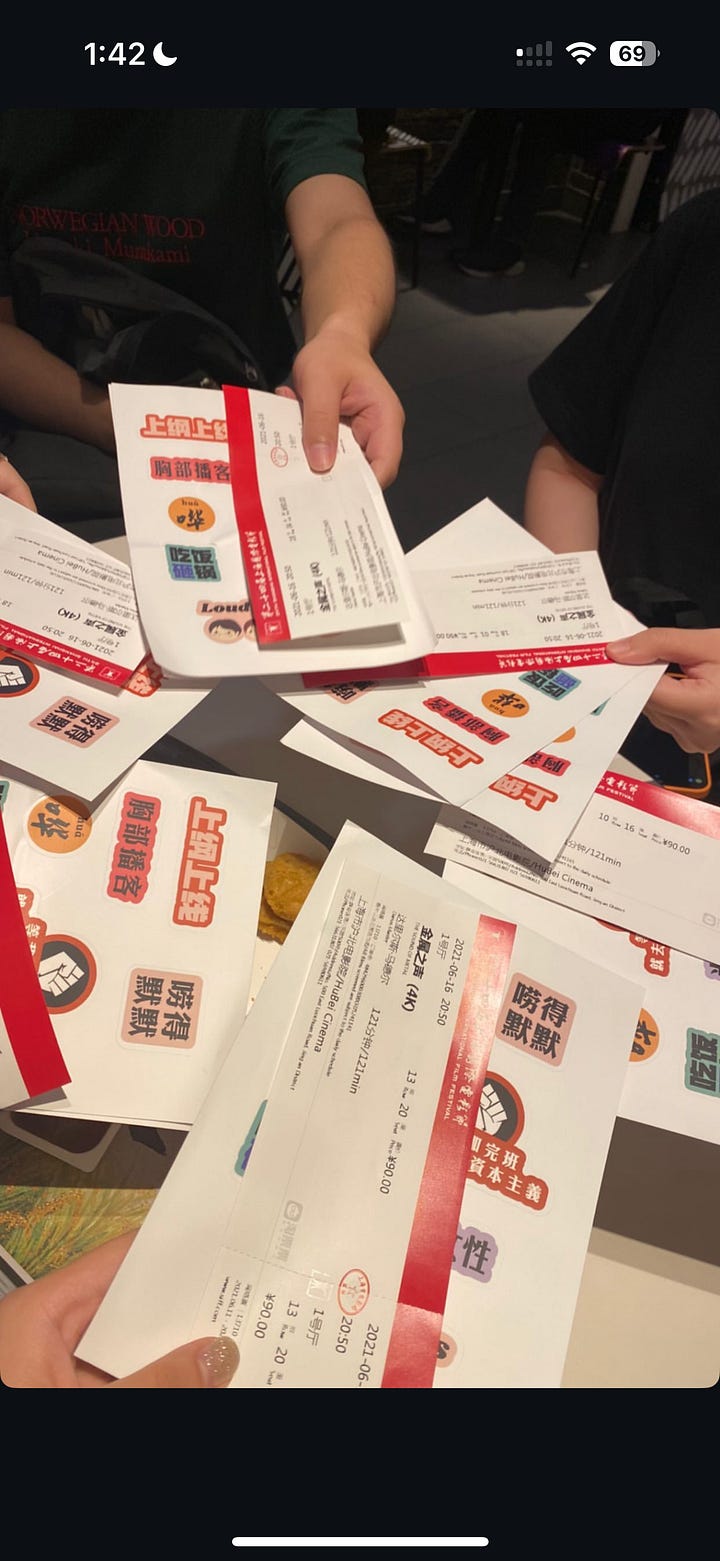

Those three months rank among the happiest of my adult life: I watched drag shows with friends at The Pearl Theater in Hongkou with a bunch of Western friends; tried on Guerlain lipstick bundle and perfume—brand gifts to my influencer friend—in her 1920s art deco apartment on Huaihai Road; attended seven screenings at the Shanghai International Film Festival, including Hong Kong movie Center Stage 阮玲玉 and Ridley Scott’s 1991 feministic masterpiece Thelma & Louise; and found myself in a Xintiandi bar discussing Yuk Hui's Recursivity and Contingency in English with a Shanghai teenager attending high school in New England; had dinner in a Latin American restaurant and found all the guests there are South American diaspora living in Shanghai.

Post-COVID, Shanghai is no longer the city of 2021. The lockdown, the White Paper protests, the catastrophic reopening, plummeting real estate values, and economic decline have all taken their toll. The city still making sense of its trauma.

I remember visiting Shanghai as a child, when nearly half the tourists were foreigners. In 2025, non-Asian faces are rare on the streets. A trending topic on Xiaohongshu during my stay neatly captured three concurrent social news: "Koreans are in Shanghai, Americans are on Xiaohongshu, and Chinese are in Myanmar." While Korean tourists are indeed visible throughout Shanghai, thanks to China's new visa-free policy, I can't help but feel that Shanghai—once China's most globally connected and cosmopolitan city—has never felt more isolated and disconnected from the world than it does now. The COVID decoupling was real, with mounting evidence showing China's growing indifference to external perceptions. If previous openness and friendliness were performances staged for economic development and global approval, today's China increasingly regards such theatrics with undisguised disdain.

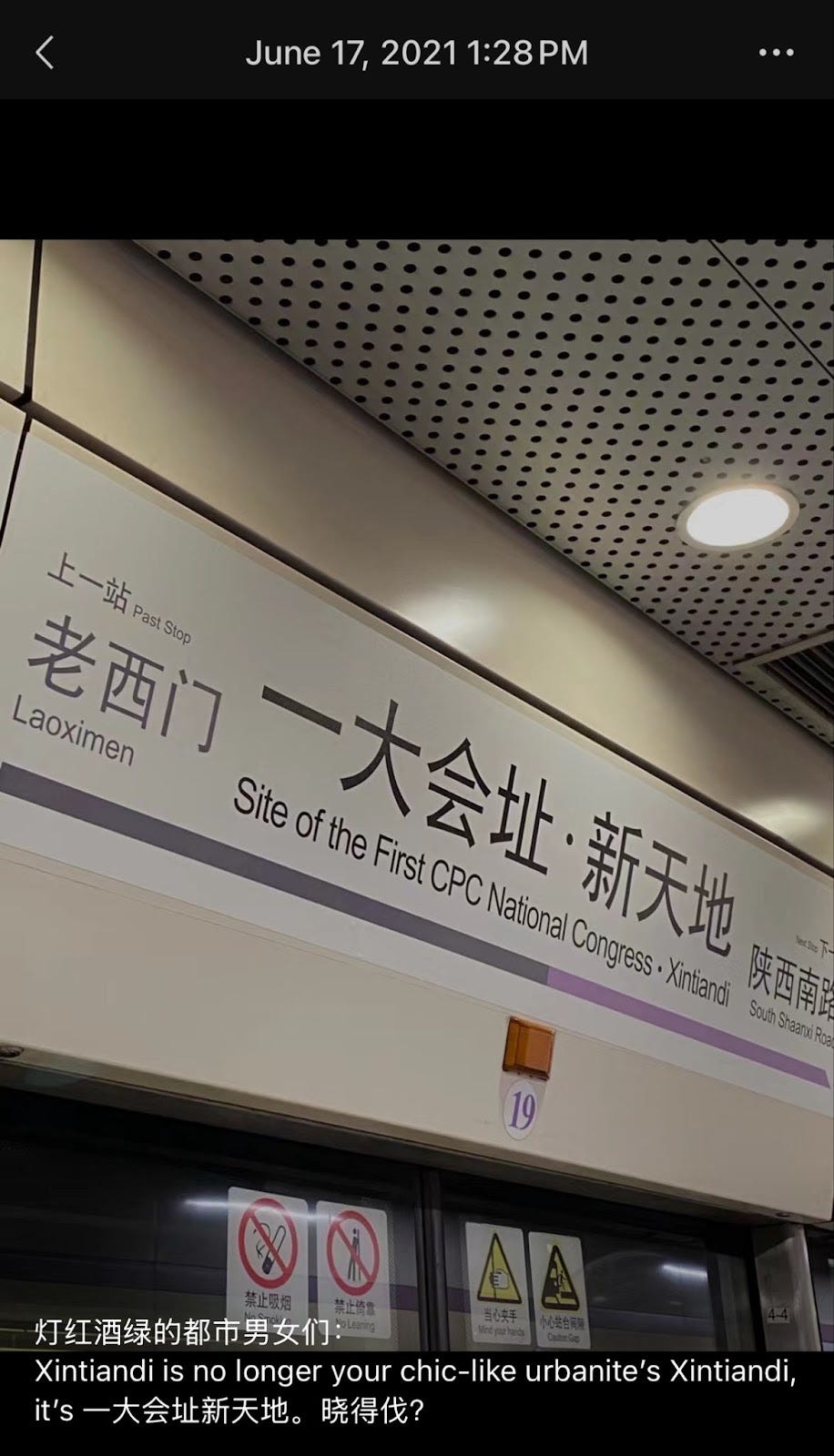

Xintiandi used to stand as a paradigmatic example of Chinese urban renewal: beginning in 1998, it emerged as both a metropolitan landmark showcasing Shanghai's distinctive culture——westernized, open 海派——and one of the city's most overtly capitalistic districts. In June 2021, the Xintiandi metro station was officially renamed to "First Party Congress Site·Xintiandi Station" to commemorate the Chinese Communist Party's centennial, owing to its proximity to the site of the Party's First National Congress. I posted a WeChat Moment teasing this verbose and awkward patriotic station name: "To all you cosmopolitan urbanites living the high life: Xintiandi is no longer your chic urbanite's Xintiandi, it's now Site of the First CPC National Congres · Xintiandi. Get it?”

Similar transformations abound. While exploring the North Bund area, I passed the former Astor House Hotel—a 19th-century six-story Victorian and neoclassical building that once hosted Einstein, Bertrand Russell, and Charlie Chaplin in the early 20th century. The Astor House Hotel has now been converted into the China Securities Museum and a patriotic education base. Inside the museum, the neoclassical architecture clashes with massive red LED screens displaying bold characters about market regulation—a visual conflict that reveals who now controls the spatial narrative.

My influencer friend who lived on Huaihai Road in 2021 has left Shanghai. Since COVID, she's received progressively fewer gifts from luxury brands. In the post-COVID era, "consumption downgrading" dominates conversations among young people, prompting English-language media to speculate whether China's luxury boom has ended. During my visit to Xintiandi's shopping center this time, I noticed many Western brand stores standing conspicuously empty. My friend

also covered the emerging trend of "money pinching becomes trendy" in her newsletter.

Datong:

If Shanghai embodied Cao Fei’s cybernetic futurism, Datong answered with its own HX Project—an archaeological loop where demolition became devotion.

I awoke from a nap, having slept for about an hour. On the high-speed train during the Chinese New Year holiday, passengers were sparse, scattered throughout the carriage that hummed with reassuring vibrations and white noise. Outside the window stretched the tall, pale sky of northern Shanxi. In the vastness of the plateau, I occasionally glimpsed isolated villages with incongruous high-rises jutting from the ground—I had reached the lands beyond the Great Wall. My final destination was Datong.

In 1900, traveling from Beijing to Datong would have required 3-6 days by carriage. Today, high-speed rail from Beijing's northern Qinghe Station reaches Datong in just two hours. This compression of time and space has fundamentally altered Datong's relationship with the capital and its place in China's urban hierarchy. With its crisp, cold climate and affordable cost of living, many Beijing professionals, exhausted by the capital's relentless pace, escape here for summer retreats. Beijingers affectionately call it their "backyard garden," a designation that simultaneously elevates and diminishes Datong.

My first ascent of Datong's new city wall introduced me to the bone-piercing cold of China's northern frontier. The wind struck my face with such sharpness that speech became impossible. Despite multiple layers of clothing, the cold penetrated everything, leaving my fingers and toes numb and frozen. I hadn't experienced such severe cold in years (later checking the weather report: approximately -20°C). I had read countless ancient poems and literary works about the northern borderlands, but only upon reaching Datong—bordered by the Great Wall to the north and adjoining Inner Mongolia—did I truly comprehend its historical significance as an imperial frontier.

Datong embodies a unique chapter of Chinese history as a crucial link in the Silk Road and ethnic integration. Historically, it served as the Northern Wei Dynasty's capital, the Western Capital of both Liao and Jin Dynasties, and a major military fortress during the Ming and Qing eras. Notably, its most prosperous periods occurred not under Han Chinese rule but during minority ethnic governance. When reading Datong's official city promotional materials, you can sense a directness in how the city wants to advertise its glorious history. They typically describe their romantic non-Han past, then immediately emphasize China's ethnic integration and cultural fusion.

The city walls of Datong surpass even Xi'an's famous fortifications in height, grandeur, and elegance. Walking the ramparts, you face a Buddhist pagoda anchoring one corner. These imposing walls encircle Datong's old city, where the aesthetic remains remarkably consistent, with virtually no tall buildings. This spatial and visual antiquity saturates perception completely. It's difficult to reconcile the ancient cityscape before my X timeline about AGI, Crypto, and Silicon Valley’s technological accelerationism.

Datong resembles many ancient Chinese cities that have laid-back development—simultaneously awaiting modernity's arrival while longing for a return to China's past. The moat beside the city wall has frozen solid, where children and adults bundled in thick coats skate and play on the ice. Entering through the eastern gate, the imposing arched entrance divides space into ancient and modern with my step. Once inside, the Ming Dynasty's Fahua Temple emerges, wreathed in incense. In this moment, China seems to have bypassed the suffering of the 19th and 20th centuries—as though this city has remained unchanged for millennia.

Yet Datong's ancient city story bears no resemblance to "tranquility." Its restoration involved quintessentially Chinese political maneuvering and a massive relocation affecting precisely 23,888 households. The serenity of its ancient spaces belies the tumult of their creation, a contradiction central to China's approach to historical preservation.

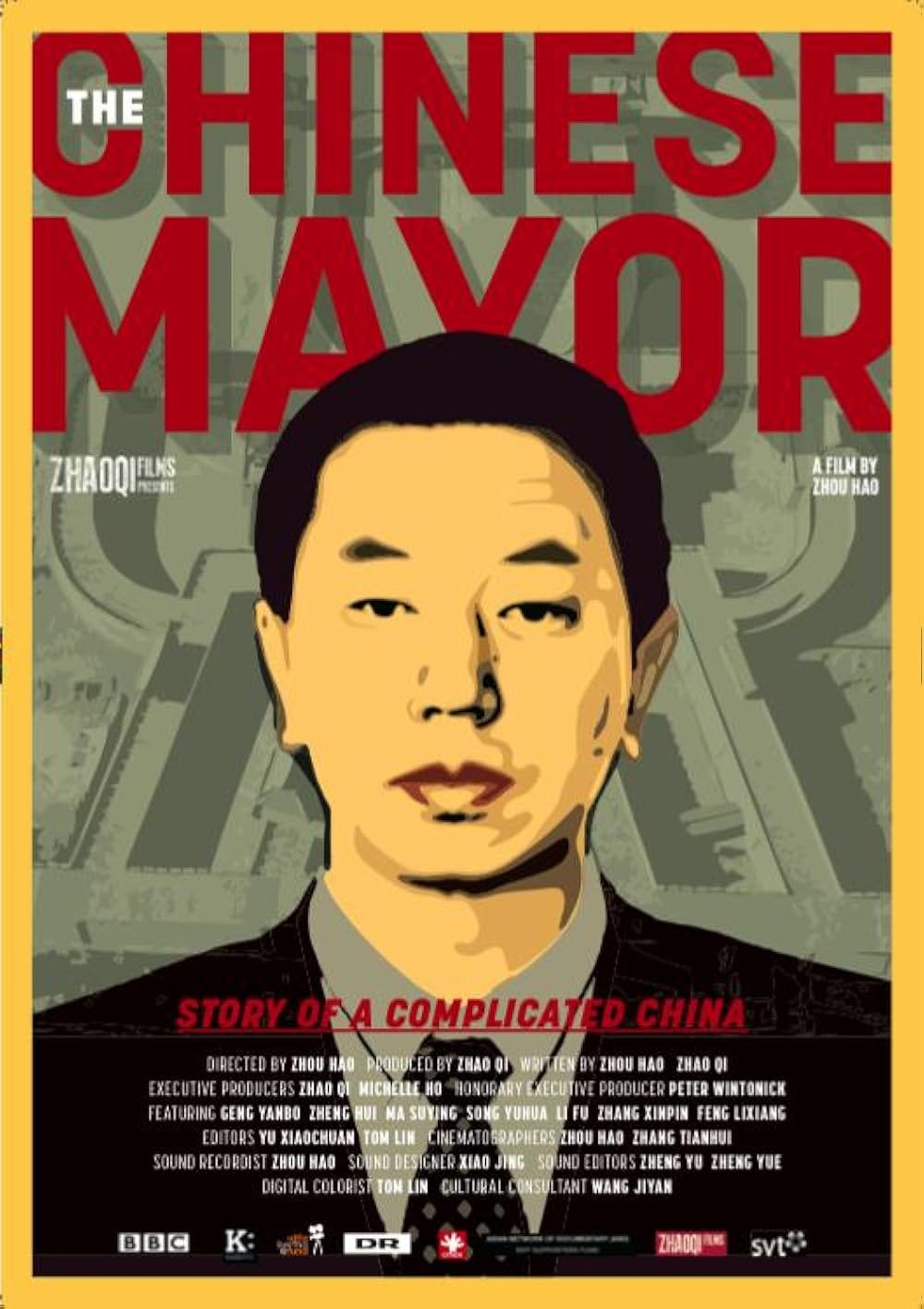

This ancient Datong rises inseparable from Geng Yanbo—China's most iconic mayor and the catalyst who transformed the city's relationship with both its past and future. Before Taiyuan claimed him, Datong shaped his legend. He was also the protagonist of the BBC award-winning documentary The Chinese Mayor, a bureaucratic Elon Musk of municipal vision, though his moonshot aimed not for Mars but for Datong’s urban metamorphosis.

Geng's directness, ruthlessness, pursuit of performance and results, along with his eagerness and cult-like personality, mirror Elon Musk's; reportedly, he would wake at 4:30 AM to begin work and frequently visit construction sites by 6 AM to expedite progress. After The Chinese Mayor won the Sundance Film Festival in 2015, I watched it immediately and cannot forget how Geng's wife could not endure his relentless work style. She broke down crying before the camera, saying, "I'm about to jump off a building. He might as well be dead, too! Every day like this [waking at 4 AM and returning home at 10 PM], it's unbearable." If Datong under Yanbo embodies China's metropolitan growing pains, it equally showcases the near-miraculous transformations possible within this crucible.

Despite commanding strategic significance through two millennia, post-Revolution Datong faded to footnote—imagine Kentucky or West Virginia’s second city, nameless in the American mind. When I first visited Datong as an elementary school student, my impression was of a city plagued by severe sandstorms and air pollution. The streets were vast, dirty, and chaotic. Like Shanxi's many coal towns, its economy extracted wealth by extracting earth, leaving landscapes scarred and air quality metrics perpetually bottom-ranking. My father, returning from business there twenty years past, described how one’s nostrils in Datong always carried coal dust. In Datong, there's a popular rhyming saying: 'Garbage is basically cleared by the wind, sewage is basically removed by evaporation, illegal vendors are basically never caught, and the city's appearance is basically never praised.”

Geng Yanbo attempted to help this resource-depleted city find a breakthrough for transformation: using the city river as a central axis, with the old city built to the west and the new district developed to the east. His plan involved restoring Datong's dilapidated ancient city walls while demolishing the 3.28-square-kilometer old town area to construct a complex of vintage-style buildings. He sought not only to restore existing treasures but to conjure entire architectural ensembles from history's dust, rebuilding structures long vanished from living memory. His grand design included reconstructing the entire 7.24-kilometer city wall, meticulously recreated from ancient city wall blueprints—a feat demanding over 5 billion yuan and displacing precisely 23,888 households. The scope included Datong's most prosperous commercial area (Daxi Street), the city's key secondary school (Datong No. 1 Middle School), and its largest scenic attraction (Huayan Temple)—all fell within the old town redevelopment zone.

“Datong must seize this opportunity to advance,” Geng declared in the documentary, “if we fail to move forward now, history will not give Datong a second chance.” Beginning in 2008, Geng Yanbo orchestrated Datong's most audacious and sweeping transformation from his mayoral throne. This radical relocation plan earned him the nickname Demolition Mayor, yet his vision reached beyond mere destruction toward resurrection and replication.

Geng's dramatic reinvention realized a dream Beijing had abandoned: Liang Sicheng's visionary "One Axis, Two Cities" concept. Liang—son of famed revolutionary Liang Qichao, educated at the University of Pennsylvania's architecture department in the 1920s, and revered as the “father of modern Chinese architecture"—has experienced his own renaissance in recent years. Like Datong itself, Liang's dedication to preserving ancient structures has found new appreciation in contemporary China. This plan ingeniously resolved the tension between preservation and development by separating them spatially. Beijing rejected this wisdom and demolished its ancient walls—a decision still mourned as the capital's greatest urban planning failure.

What Beijing refused, Datong embraced. The One Axis, Two Cities 一轴双城 vision that Liang Sicheng lamented for years found rebirth decades later in Datong, with Geng Yanbo emerging as Liang's most diligent and faithful student—though they never met. Along Datong's ancient wall, Geng quietly established a memorial honoring Liang Sicheng and Lin Huiyin's contributions to preserving China's architectural heritage. The memorial, designed like a Qing Dynasty courtyard home, features bronze statues of the couple in its central garden. Meanwhile, the people's determination to erect a statue of Geng himself was overturned by bureaucratic obstacles, yet he ascended to near-mythic status in their hearts.

After enduring the hardships of relocation and accumulating substantial external debt, Datong experienced a nearly miraculous renaissance. Citizens came to recognize Geng's foresight and courage in transforming their city—he became Datong's Da Vinci of urban renewal. When authorities reassigned him in February 2013, thousands of residents spontaneously gathered at the East City Wall Square and other locations, signing petitions and raising banners pleading for him to stay. Many citizens even knelt in supplication, begging him not to leave—a powerful scene captured in The Chinese Mayor documentary. Whenever I speak with taxi drivers or shopkeepers in the old city about Geng, they express near-unanimous admiration. Many reverently call him "Lord Geng"—the highest Confucian tribute commoners can bestow upon an official.

On my final night in Datong, the cold still gripped the air. Wandering through the ancient city, I ducked into a wood carving shop seeking warmth. The owners—a couple in their mid-thirties—noticed my shivering and quickly brewed a pot of Wuyi Mountain red tea. Learning I had come from Beijing, the woman eagerly unlocked her Xiaomi phone to ask how she might use DeepSeek to manage the shop's Xiaohongshu account. As I suggested which content might suit AI writing, our conversation unfolded naturally.

The shopkeeper's family had practiced roof tile carving and woodcraft for four generations. The most prominent wall displayed photographs of his father, uncle, and two brothers—a dynasty of artisans. Beneath these portraits sat several round, gray antique roof tiles adorned with mythical beast carvings, traditional guardians meant to protect those beneath the eaves. The owner revealed that after the demolition of their ancestral home in the old city, he had secretly returned to the ruins to retrieve these tiles. Now settled in the "new ancient city" in his "new ancient house," he placed these artifacts in his shop as ancestral blessings for his business. When speaking of his demolished home, the shopkeeper's regret mingled with a surprising sense of civic duty—"cities must develop," his tone suggested.

As he described the challenges of running his business, I reflected how nearly every ordinary person I'd met in Datong complained about their low income, yet each seemed to blame some broader economic environment rather than local circumstances. "What do you think of Geng Yanbo?" I asked curiously. Instead of answering directly, he pointed to a small wooden sculpture beside the roof tiles: "The people of Datong wanted to erect a statue for Mayor Geng, but they wouldn't allow it. I carved this myself and keep it here for protection." Looking closely, I saw the miniature depicted Geng with head lowered and hands clasped behind his back, apparently inspecting construction work—a posture of complete dedication.

In China, time flows at different rates: skyscrapers completed in months, an ancient city entirely renovated in less than a decade. China has transformed immensely. Yet in Datong, certain things seem barely changed at all. As Peter Hessler writes in his non-fiction book Other Rivers: "Like so many things in China, it feels like a contradiction: everything has changed; nothing has changed."

The ancient walls that now stand pristine around Datong are simultaneously ancient and brand new—a physical manifestation of China's approach to history itself. In their shadow, both time and identity become fluid, as residents like the woodcarver adapt to lives in "new ancient houses," carving tributes to the man who demolished their homes.

Taiyuan, family history:

In college, I read English historian Tony Judt's "The Memory Chalet." That small cottage in an expensive Swiss ski resort, visited with his family years before, occupied the deepest and most emotionally resonant place in this English intellectual's mind. After being diagnosed with ALS, Judt wrote an autobiography named after this cottage—a mental space to store his visual and spiritual memory from his deepest consciousness.

If I had such a chalet, it might be my junior year dormitory in suburban Orange County, Southern California. The fierce 3 PM sunlight would pierce through white venetian blinds, greeting my white IKEA desk, the cheapest one I could find. Or perhaps it would be in London, where I wrote my thesis in LSE's most affordable student housing—a room perfumed with coffee, laundry detergent from bedsheets, and dust rising from the old carpet. In that room, I battled depression beneath London's overcast skies while facing seemingly insurmountable barriers: where to work after graduation, how to secure a work visa.

Yet if I allow my consciousness to sink deeper, a clearer spatial memory emerges. It is a garden.

This garden lies in Taiyuan, within the residential complex of our first home after moving there when I was seven. It features a white-domed pavilion where elderly men play Chinese chess in summer, and roses of every hue line narrow walking paths. The garden brims with plants of various colors—the most common and typical ornamental vegetation in northern Chinese neighborhoods—alongside several tall willows.

In my memory, this garden is vast, nearly an entire universe. My parents, perpetually busy, rarely pick me up to or from school. Each day after classes, my solitary journey home became an extraordinary adventure. One spring afternoon, walking through this garden where roses grew so vigorously they reached my eye level. Once I observed a single rose with such complete absorption and attention that time and space ceased to exist. The garden held many mystical vistas. I would recite Du Fu's ancient poetry—"The late sun beautifies mountains and rivers; spring breeze carries the fragrance of flowers and grass"—earnestly trying to detect that promised "fragrance" in the air, walking alone in the garden's safety and poetic embrace. As a child, I sensed my parents' struggle to settle in Taiyuan; our home vibrated with financial and existential anxiety. The internet and this garden became the most intimate, secure sanctuaries.

For many years afterward, this garden withstood Taiyuan's rapid urban transformation. On my recent visit, the winter garden stood serene and desolate. In the white pavilion, the marble table and four stone stools remained. Rose branches, now bare, awaited next spring's renewal. Beyond this small garden, everything in Taiyuan had changed.

Eileen Chow, a professor at Duke University who frequently graces a podcast I co-host, once captured on social media the exquisite melancholy of parenthood. I couldn’t find the original post, but it writes like this:

Raising a child is like repeatedly falling in love with somebody only to watch that person drift away and be replaced by another beautiful person who you fall in love with all over again while you mourn the loss of who they once were.

These words, though intended for the metamorphosis of children, perfectly articulate my feelings toward Taiyuan's changing cityscape. Each return requires recalibrating my internal map—muscle memory leading me down remembered alleyways now transformed into eight-lane thoroughfares. The city unveils itself anew with each visit, yet I harbor persistent grief for the Taiyuan of my childhood.

Taiyuan's urban transformation mirrors countless Chinese cities. In the years since my departure (2012), two subway lines have opened (making Taiyuan mainland China's 39th city with metro service), and every taxi has been replaced with BYD electric vehicles.

I walked into the new mall—gleaming and vast—built atop the demolished shopping center that housed so many childhood memories: celebrating my friend's 12th birthday at KFC, purchasing my favorite yogurt from the underground supermarket, buying flowers for our teacher on Teachers' Day.

Now this new five-story building is before me. Contemporary China abounds with such complexes: massive buildings serving multiple functions. Inside, brands range from luxurious to affordable—satisfying virtually every consumer desire. Entering the atrium, an enormous glass-encased Huawei store dominates the space. The first floor sells phones, computers, touchpads, and various gadgets, while the second floor showcases several of Huawei's newly developed DriveONE electric vehicles. In a second-tier city like Taiyuan, those seeking automotive status still inevitably choose Porsche, Mercedes, or Audi. Huawei or Xpeng electric vehicles rarely appear on Taiyuan's streets, let alone the more expensive Xiaomi models. Far more common are the more affordable BYDs and Hongqi brands, with occasional Teslas making appearances.

In the days before Chinese New Year, my family departed from Taiyuan—journeying to our true "home" where my grandparents live. In Chinese family consciousness, the true "home" resides where the elders dwell. Our destination was Huozhou, a county-level city in Shanxi province, my grandmother's residence, my extended family's anchor, and my birthplace.

Whenever I see a "strong woman" in any film—whether Ellen Ripley in James Cameron's "Aliens" or “my grandmother” in Zhang Yimou's "Red Sorghum"—I'm reminded of my own grandmother, a strong woman from Shandong province. At eighty-one, she maintains robust health and crystalline clarity of mind. Apart from one hospitalization after contracting the virus when COVID restrictions lifted, she has remarkably avoided hospitals for years.

My grandmother is a living memory chalet—a repository of stories spanning decades of turbulent Chinese history. If my Taiyuan garden preserved the intimate, personal experiences of childhood, she preserves something far more expansive: the collective trauma and resilience of generations navigating political upheaval.

You know that feeling when you hear your family stories repeatedly—it's like assembling an immense puzzle across time and space. The broad composition remains clear, but details shift constantly; perhaps the ten-year-old me added numerous pieces, then my fifteen-year-old self contributed more... each iteration growing increasingly complex. Listening to my father and grandmother recount our "Shandong ancestral roots" delivers precisely this experience. This visit revealed that during the Land Reform Movement, my landlord ancestors' houses and properties were confiscated. The elementary school my father and his brothers attended was converted from our seized ancestral home.

Outside the elementary school stands a statue of my great-grandfather—the biggest landlord in Dongming County. The revolutionaries unable to find him in person, erected this likeness so that common people could point at this counter-revolutionary while cursing. My legendary great-grandfather, sensing dangerous political winds before the Land Reform in 1949, fled Shandong and wandered through Hong Kong, Tibet, Wuhan, and beyond—nearly forty years of nomadic existence. Not until the 1980s did he dare return to his Shandong homestead. Four decades of the landlord's absence meant my great-grandmother endured not only child-rearing responsibilities, but also the relentless political turmoil, personal humiliation, and torment that began with the Land Reform movement and continued without respite.

During another episode amid the Cultural Revolution, when Red Guards occupied my uncle's junior high auditorium to denounce "landlord wives," my uncle was specifically summoned by teachers to witness the spectacle. Only then did he discover that the two evil landlord women kneeling in the hall were actually his grandmothers—my great-grandmother and great-grandmother-in-law. They knelt with white high-pointed caps on their heads, hair disheveled, expressions vacant. Later that day, my uncle returned home and wept uncontrollably. My father, too young to understand, couldn't comprehend why his normally composed older brother had lost control of his emotions.

As grandmother and father shared these stories at our Chinese New Year's Eve table, they were unconsciously processing—continuously, for decades—countless unresolved family traumas. These stories, some complete and others fragmentary, compose the ever-shifting constellation of those puzzle pieces of Wang’s family history.

After recounting the turbulent sixties, grandmother pivoted unexpectedly toward the future. "I simply want to see how long I can live," she said, "to witness what shape the coming days will take." At eighty-one, she has borne witness to China at its lowest depths, its greatest heights, and the valleys between.

I recalled during the Zero Covid policy when my cousin sent videos through WeChat showing grandmother's neighborhood under lockdown: five massive drones hovering overhead, simultaneously announcing safety measures and discouraging residents from leaving their homes, while methodically spraying disinfectant through the air. I wondered what thoughts might have crossed my grandmother's mind—she who traversed such dark times—as she watched these flying robots patrol her skies.

During my 1-month wanderings through China, I tried to think of some smart theory of technological transformation—to parrot some abstract framework that contains words like “dialectic” or “post-capitalism.”

But my attention veered inexorably back to the specific, to the tangible: my grandmother's Xiaomi phone, the woodcarver's miniature statue of Mayor Geng, those ancient roof tiles rescued from demolished homes.

This is China's reality of development, not universal or abstract, but embedded in the particular. Not a theory, but a garden where roses grow eye-level to a child, where drones patrol skies that have witnessed change. This is the China I grew up in: impossible to map, yet perfectly clear in my vision.

Thank you, Zac, Yiran, io, and Amy for reading the draft and giving me feedback.

I'm very attracted to your ruminations on the concepts of home and Homeland in the postmodern era especially concerning the ancient historical roots of China and its rapid evolution in the last few decades. I went through a phase where I was writing a lot of poetry and the Chinese poets were among my favorite.

I don't have the ability to travel much so living vicariously through others is my primary mechanism for empathy with the wider world. I keep watching documentaries trying to understand what it might feel like to live in a world where you can go from poverty to riches, the country of tradition to big cities, and yet be perpetually misunderstood by the wider world as China has.

We take a piece of home and Homeland with us wherever we go, whether we realize it or not. As such I enjoy autobiographical and travel blogs like people such as you or Jasmine find write from time to time.

As your literary fan, unfortunately I cannot adequately describe the sensation of watching your relationship with words, storytelling and narrative. The image of you crying tears for a dear book suffocates my awareness of the hero's journey of the author. It fills me with longing for things I cannot name, own and belonging I will likely never possess.

At the end of the day it's not the mechanics of the observer that matters, it's that the act is a fundamental activation of mirror neurons. But in the process of identification the reader, I cannot quite reach your level. I know there's futurism hidden in the history, and genius playing hide and seek in the stories.

this is arresting - and makes me think of my own weird road trip to Datong (you can drive from Beijing in 3hrs but the coal traffic meant the return journey took more like 6)